Ananda Behera v. State of Orissa (1955)

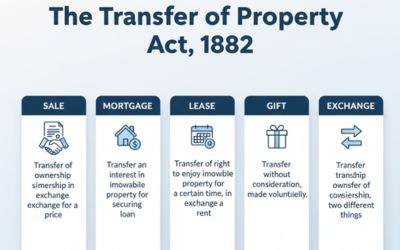

Profit a prendre counts as a benefit arising from land and forms part of immovable property.

Quick Summary

This case explains that a right to enter land and take natural produce—here, fish from Chilka Lake—is a profit a prendre. In Indian law, such a right is a benefit arising from land and therefore part of immovable property. The petitioner’s fishing licence was a personal contract; after the estate vested in the State under the Orissa Estates Abolition Act, the State was not bound by that contract in writ proceedings.

Issues

- Does a right to catch and carry away fish from a lake amount to a profit a prendre?

- If yes, does it form part of immovable property in India?

- Could the petitioner enforce the fishing licence against the State through a writ under Articles 19(1)(f) and 31(1)?

Rules

- Profit a prendre is a benefit arising out of land (e.g., taking fish, timber, minerals).

- Benefits arising from land are treated as immovable property and pass with the land unless excluded.

- Personal contracts under the Sale of Goods Act do not bind the State on vesting, and are not enforceable by writ.

Facts (Timeline)

Licence: Ananda Behera obtained a licence from the Raja of Parikud to catch and take all fish from specified parts of Chilka Lake.

Statutory Vesting: The Orissa Estates Abolition Act, 1951 vested the estate, including the lake area, in the State of Orissa.

Dispute: The State declined to honour the earlier licence under the new regime.

Writ Petition: The petitioner alleged violation of Article 19(1)(f) and Article 31(1), and argued the licence was a sale of future goods, not about immovable property.

Arguments

Appellant (Ananda Behera)

- The licence allowed catching and taking fish; this was a sale of future goods under the Sale of Goods Act.

- Therefore, abolition of estates should not defeat his personal right to fish.

- State’s refusal infringed property rights under Articles 19(1)(f) and 31(1).

Respondent (State of Orissa)

- The right to enter the lake and take fish is a profit a prendre, i.e., a benefit from land—thus immovable property.

- On vesting, the State took the estate free from such private licences unless saved by law.

- A writ cannot enforce a personal contract against the State.

Judgment

The Supreme Court held that the lake formed part of immovable property, and the petitioner’s right to enter and take fish was a profit a prendre. Such a right is a benefit arising from land and falls within immovable property in India. The licence remained a personal contract and could not be enforced against the State through a writ. The petition was dismissed.

Ratio (Core Principle)

Profit a prendre—the right to take natural produce from another’s land—is a benefit arising from land and is treated as immovable property in Indian law. Personal licences of this kind do not bind the State post-vesting unless protected by statute.

Why It Matters

- Clarifies how Indian law classifies resource-taking rights like fishing and timber.

- Separates property rights from personal contracts in public law challenges.

- Guides drafting of licences around lakes, forests, and minerals after land reforms.

Key Takeaways

- Fishing rights from another’s land/waters = profit a prendre.

- Benefits from land = immovable property.

- Personal licences are not enforceable by writ against the State.

- Sale-of-future-goods argument fails where the right arises from land.

Mnemonic + 3-Step Hook

Mnemonic: F.I.S.H. — From land, Immovable, State not bound, Hire (licence) is personal.

- Spot the right: taking natural produce from land/water.

- Classify: benefit from land ⇒ immovable property.

- Enforce: personal licence ≠ writ against State post-vesting.

IRAC Outline

Issue: Is fishing in Chilka Lake a profit a prendre forming part of immovable property, and can it be enforced against the State by writ?

Rule: Profit a prendre is a benefit arising from land and is immovable property; personal contracts do not bind the State in writ proceedings.

Application: The licence allowed entry and removal of fish (natural produce). This fits profit a prendre. After abolition, the State took the estate; the licence, being personal, was not enforceable by writ.

Conclusion: Yes, it is a profit a prendre and part of immovable property; no writ relief—petition dismissed.

Glossary

- Profit a prendre

- Right to enter another’s land and take natural produce (e.g., fish, timber, minerals).

- Immovable property

- Property that is not movable; includes benefits arising from land.

- Vesting

- Transfer of ownership to the State under a statute.

- Writ

- Extraordinary remedy to enforce public law rights; not for private contract enforcement.

FAQs

Related Cases

- Cases on forest produce and minerals as profits a prendre

- Decisions on writs and contractual rights post-land reform

Share

Related Post

Tags

Archive

Popular & Recent Post

Comment

Nothing for now