Kokilambal and Ors. v. N. Raman

AIR 2005 SC 2468 • Supreme Court of India • Property / Settlement Deed

Quick Summary

This case settles a simple but important point: did the nephew, Varadan, get full ownership during the aunt’s life, or only after her death?

The Supreme Court said the deeds gave Varadan contingent rights that would vest only after Kokilambal’s death. Because Varadan died earlier, nothing vested in him. So, she could revoke the deeds and settle the properties afresh. The appeal was allowed.

Issues

- Whether the settlement deed created a vested interest in favour of Varadan during the settlor’s lifetime or only upon her death.

- Whether the settlor, Kokilambal, could revoke the deeds and make fresh settlements after Varadan’s death.

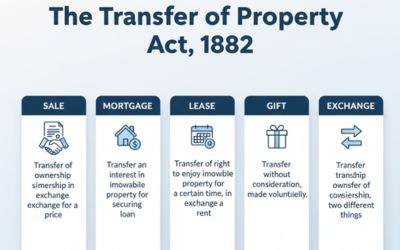

Rules

- If the deed keeps control with the settlor or makes ownership depend on a future event, the beneficiary does not get absolute rights.

- A contingent interest arises only if the stated future event occurs.

- The settlor’s intention must be read from the deed as a whole.

Facts (Timeline)

Arguments

Appellant

- Deeds postponed vesting until the settlor’s death; hence no absolute title in Varadan during her life.

- Joint consent clause kept control with the settlor; interest remained contingent.

- Since Varadan predeceased the settlor, the contingency failed; revocation was valid.

Respondent

- Deeds gave a present transfer with only enjoyment postponed; thus, a vested interest existed.

- Revocation after such vesting was impermissible.

Judgment

The Supreme Court allowed the appeal.

- The deeds clearly stated that full ownership would pass only after the settlor’s death. So Varadan had no absolute title during her life.

- Because Varadan died earlier, the contingency did not occur. The deeds did not vest the property in him.

- Kokilambal was free to revoke and execute fresh settlements, which stand upheld.

Ratio Decidendi

Read the deed as a whole. Clauses that postpone vesting till the settlor’s death and require joint consent for alienation show a contingent interest, not a present vested transfer. Predeceasing the settlor defeats the contingency.

Why It Matters

- Helps drafters avoid confusion between vested and contingent interests.

- Shows that control clauses (joint consent, life enjoyment) can keep ownership with the settlor till death.

- Guides families on the effect of a beneficiary dying before vesting.

Key Takeaways

- State vesting time in plain words—“title passes on the settlor’s death”.

- If joint consent or control remains, it likely points to a contingent interest.

- If the beneficiary dies first, the settlement may fail; revocation becomes possible.

Mnemonic + 3-Step Hook

Mnemonic: “DIE–CONSENT–VEST”

- Die: Vesting waits till settlor’s death.

- Consent: Joint consent = control with settlor.

- Vest: If beneficiary dies first, no vest.

IRAC Outline

Issue

Was Varadan’s interest vested during the settlor’s life, or contingent on her death? Could she revoke after his death?

Rule

Read the deed wholly. Control + postponed vesting = contingent interest; vesting only on the stated event.

Application

Clauses required joint consent and said full title passes after death. Varadan died earlier; contingency failed.

Conclusion

No absolute title in Varadan. Revocation and fresh settlements by Kokilambal were valid. Appeal allowed.

Glossary

- Vested Interest

- Right is fixed now, though enjoyment may be later.

- Contingent Interest

- Right depends on a future event; if the event fails, the right fails.

- Revocation

- Calling back a deed before rights finally vest.

FAQs

Related Cases

Focus on Sections about vested and contingent interests; drafting clarity.

Cases explaining control-retaining clauses and their effect on vesting.

Share

Related Post

Tags

Archive

Popular & Recent Post

Comment

Nothing for now