Proposal under Indian Contract Act 1872

A proposal is when one person makes an offer to another person, intending to create a legally binding agreement. It shows their willingness to do or not do something, which becomes the basis of a contract.

According to Section 2(a) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, “when one person signifies to another his willingness to do or to abstain from doing anything, with a view to obtaining the assent of that other to such act or abstinence, he is said to make a proposal”.

A proposal must be definite and specific in its terms, and it should be communicated to the other party with the intention of obtaining their acceptance. Once the other party accepts the proposal, it becomes a promise, and the terms of the contract bind the parties. If the proposal is not accepted, it will be considered a mere invitation to offer, and it will not create any legal obligation between the parties.

Examples

ABC Ltd. offers to sell its products to XYZ Ltd. for a certain price. The offer is made in writing and sent via email to XYZ Ltd. This offer is a proposal, and if XYZ Ltd. accepts the offer, it becomes a binding contract.

John offers to sell his car to Jane for a certain amount. The offer is made orally during a conversation between them. This offer is also a proposal, and if Jane accepts the offer, it becomes a binding contract.

Builders Co. submits a proposal to the City Council for building a new bridge. The proposal includes details of the project, such as cost, timeline, and specifications. This proposal is an offer to enter into a contract with the City Council, and if the agency accepts the proposal, it becomes a binding contract.

What is an invitation to offer?

An invitation to offer is a communication that encourages someone to make an offer or proposal but is not an actual offer itself. It invites negotiations or discussions, which may or may not lead to a contract.

In simple terms, an invitation to offer starts the negotiation process and does not create a legal obligation to accept any resulting offer.

Examples of an invitation to offer include advertisements, price lists, catalogues, and displays of goods in a shop window or online store. These are not binding offers but invite customers to make an offer to purchase.

For example, a shop owner displaying goods in their store window is inviting customers to make an offer to purchase those goods. The customer's offer to buy at a certain price is a proposal, and the shop owner's acceptance of the proposal creates a binding contract.

Landmark Cases Dealing with Invitations to Treat/Offer

Pharmaceutical Products of India Ltd. v. Gwalior Chemical Works Ltd. (1960)

In this case, the court held that a price list is an invitation to treat and not an offer or proposal. The court determined that a contract is only formed when an offer is made by one party and accepted by the other.

Fisher v. Bell (1961)

This case established the principle that a display of goods in a shop window or on a shelf is generally an invitation to treat and not an offer. The customer’s offer to purchase the goods at a certain price would constitute a proposal, and the shop owner’s acceptance of the proposal would form a binding contract.

Harvela Investments Ltd. v. Royal Trust Co. of Canada (1986)

This case established the principle of the “invitation to tender,” which is a process by which a party invites potential contractors to submit bids for a project. The court held that an invitation to tender is not an offer, but rather an invitation to submit offers.

Mohanlal v. Kashiram (1962)

In this case, the court held that an advertisement for the sale of property is an invitation to treat and not an offer. The court ruled that a contract is only formed when an offer is made by one party and accepted by the other.

Harvey v Facey (1893)

In this case, the plaintiff (Harvey) telegraphed the defendant (Facey) asking if he would sell certain property and, if so, at what price. The defendant replied with a telegraph that simply stated the lowest price he would accept for the property. The plaintiff then claimed that the defendant had made an offer to sell the property at that price, which he had accepted by his subsequent telegraphs.

The court, however, held that the defendant’s telegraph was not an offer to sell the property, but rather a mere statement of the lowest price he would accept. The court ruled that the defendant had not made any offer, and therefore there was no contract between the parties.

The court further explained that an invitation to treat is not an offer, but rather an invitation to commence negotiations or discussions. The court held that the defendant’s telegraph was an invitation to treat, and not an offer to sell the property.

Intention to Create a Legal Relationship

The intention to create a legal relationship is a crucial element in forming a contract. It refers to the parties' intention to establish a legally binding agreement, one that can be enforced by law.

Generally, the law presumes that parties intend to create a legal relationship when they enter into a contract. However, this is not always the case, particularly in social or domestic arrangements. For instance, if friends agree to meet at a café, there typically isn't an intention to form a legally binding agreement.

For a contract to be enforceable, the intention to create a legal relationship must be present at the time the agreement is made. This means both parties must have a mutual intention to establish legal relations.

The intention to create a legal relationship can be either expressed or implied. It may be explicitly stated in the contract, where the parties clearly indicate their intention to form a legally binding agreement. Alternatively, it can be implied from the circumstances surrounding the agreement. For example, if someone provides a service and receives payment, there is an implied intention to create a legal relationship.

If the parties do not intend to create a legal relationship, the agreement will not be enforceable as a contract. Therefore, determining the presence or absence of this intention is essential for establishing the validity of a contract.

Balfour v Balfour

Balfour v Balfour is a landmark case in contract law that addresses the issue of intention to create a legal relationship. The case was decided by the English Court of Appeal in 1919.

Facts:

Mr. Balfour was a British civil servant stationed in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1915. His wife, Mrs. Balfour, stayed in England due to health reasons. Before leaving, Mr. Balfour promised to pay his wife a monthly allowance of £30 until she could join him. Later, the couple separated, and Mrs. Balfour sued her husband for breach of contract, seeking the unpaid allowance.

Decision:

The court held that there was no contract between Mr. and Mrs. Balfour. The promise made by Mr. Balfour was considered a social arrangement between husband and wife, not intended to create a legal relationship. The court emphasized that not all agreements between family members or spouses are legally binding. For a contract to be enforceable, there must be an intention to create a legal relationship.

Key Points:

- The court ruled that social or domestic agreements typically do not create legal obligations.

- The absence of an intention to create a legal relationship means there is no consideration, which is essential for a contract.

- Mrs. Balfour did not provide any consideration in exchange for her husband's promise.

Principle Established:

A social or domestic agreement, made without an intention to create a legal relationship, does not give rise to a binding contract.

Merritt v Merritt

Merritt v Merritt is another landmark case in contract law dealing with the intention to create a legal relationship. The case was decided by the English Court of Appeal in 1970.

Facts:

Mr. and Mrs. Merritt were a married couple who had separated but not yet divorced. They jointly owned a house and agreed to transfer ownership to Mrs. Merritt in exchange for her agreement to pay off the remaining mortgage. The couple signed a written agreement to this effect. After Mrs. Merritt paid off the mortgage, Mr. Merritt refused to transfer the ownership of the house to her. Mrs. Merritt sued for breach of contract.

Decision:

The court held that there was a valid and enforceable contract between Mr. and Mrs. Merritt. The signed written agreement was evidence of their intention to create a legal relationship, and both parties had given consideration. Mrs. Merritt agreed to pay off the mortgage, and Mr. Merritt promised to transfer ownership of the house.

Key Points:

- The court found that the parties' separation and the formal written agreement indicated an intention to create a legal relationship.

- The agreement was not a mere domestic arrangement but a binding and enforceable contract.

Principle Established:

An agreement between spouses or family members can give rise to a binding contract if there is evidence of an intention to create a legal relationship and both parties provide consideration.

Lalman Shukla v. Gauri Dutt (1913)

In this case, the plaintiff, Lalman Shukla, was employed by the defendant, Gauri Dutt, as a munim (a clerk). Gauri Dutt's nephew had gone missing, and Lalman was sent to find the boy. While Lalman was away searching, Gauri Dutt issued handbills offering a reward of Rs. 501 to anyone who found the boy.

Lalman eventually found the boy and later claimed the reward. However, he was unaware of the handbills and the reward offer when he found the boy.

Decision:

The court held that Lalman Shukla was not entitled to the reward. The reasoning was that Lalman did not know about the reward offer at the time he found the boy, and therefore, he could not have accepted the offer. For an offer to be validly accepted, the offeree must have knowledge of the offer and must act with the intention of accepting it.

Principle Established:

The case established that for a reward offer to be accepted, the person performing the act (in this case, finding the boy) must have knowledge of the offer and perform the act with the intention of accepting the reward. This underscores the importance of communication in the formation of contracts.

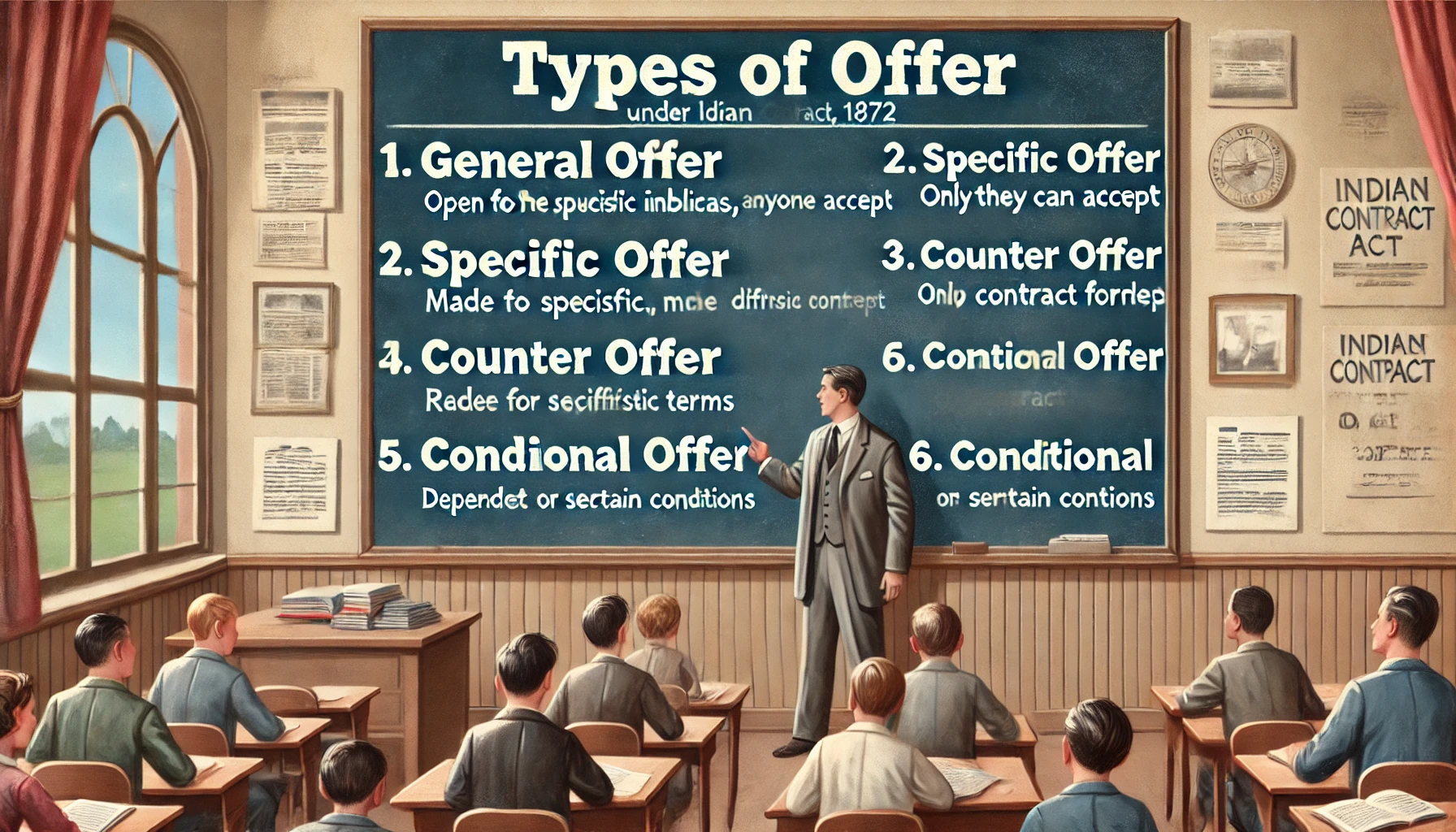

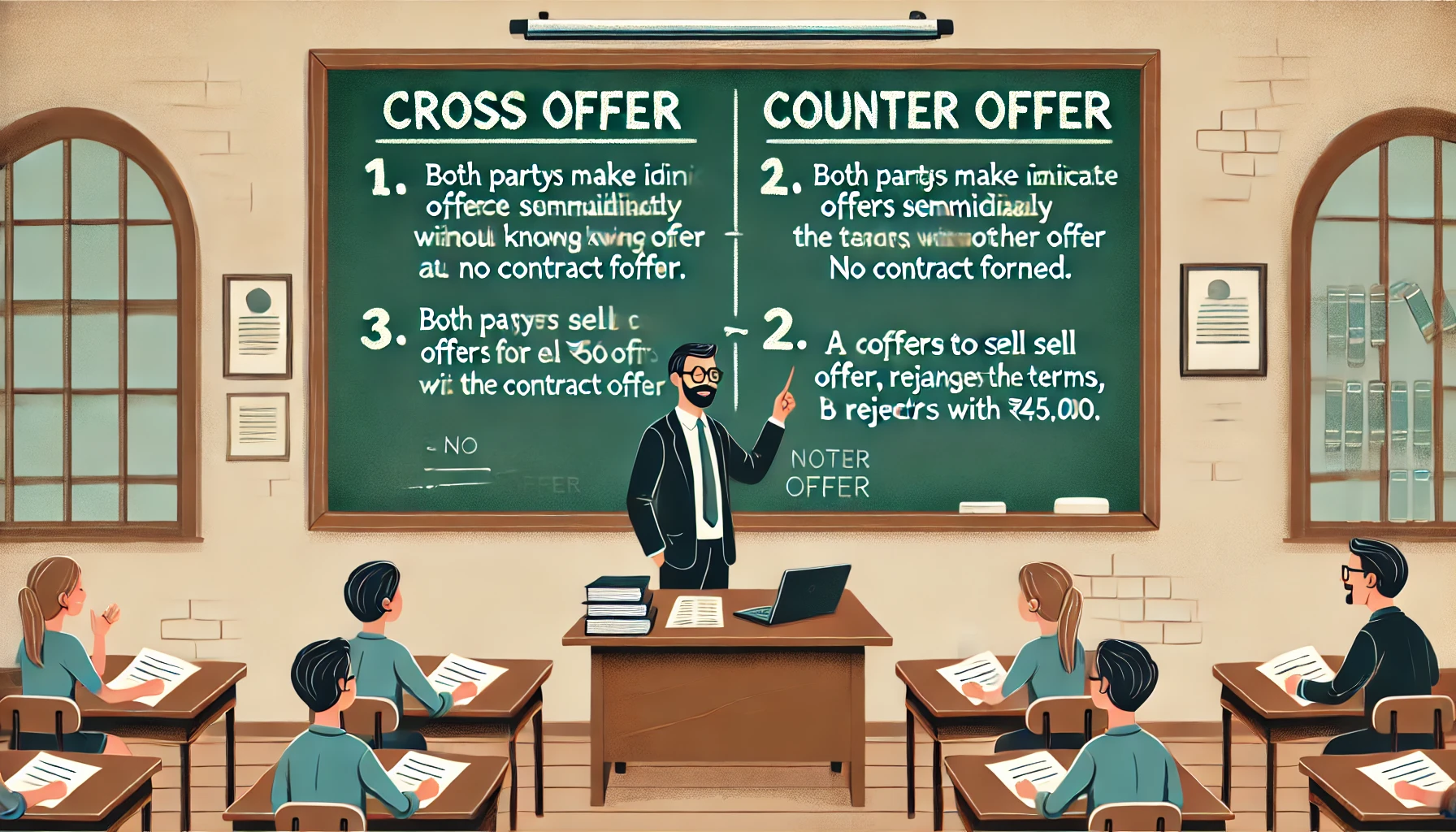

Types of Offer/Proposals: Cross Offers

A cross offer occurs when two parties make identical offers to each other without knowing that the other has made an offer. In such a situation, neither party can accept the other’s offer, as there is no clear indication of an intention to create a legally binding agreement. Here are a few landmark cases related to cross offers:

Tinn v. Hoffman (1873)

Facts:

In this case, the plaintiff and the defendant were negotiating the sale of a quantity of iron. The plaintiff sent a letter offering to sell the iron at a certain price, and the defendant sent a letter in response, also offering to buy the iron at the same price. However, neither party had received the other’s letter at the time they made their offer.

Decision:

The court held that there was no contract between the parties, as neither party had accepted the other’s offer. The court emphasized that for a contract to be formed, there must be a clear acceptance of an offer. Since both parties made identical offers simultaneously without knowledge of the other’s offer, there was no mutual assent and therefore no contract.

Counter Offer

A counter offer occurs when the offeree responds to an offer by making a new offer on different terms. This effectively rejects the original offer and puts forward a new offer for the original offeror to accept or reject. A counter offer implies that the offeree does not agree to the terms of the original offer and proposes alternative terms for negotiation. Here are a few landmark cases related to counter offers:

Hyde v. Wrench (1840)

Facts:

In this case, Wrench offered to sell his farm to Hyde for £1,000. Hyde responded by offering £950, which Wrench rejected. Hyde then attempted to accept the original offer of £1,000, but Wrench refused to sell.

Decision:

The court held that Hyde's counter offer of £950 had rejected the original offer of £1,000. Therefore, there was no longer an offer of £1,000 for Hyde to accept. The case established the principle that a counter offer effectively rejects the original offer and puts forward a new offer for consideration.

Principle Established:

A counter offer nullifies the original offer and proposes a new set of terms, requiring acceptance from the original offeror to form a contract.

Specific and General Offers

In contract law, an offer is a proposal made by one party (the offeror) to another party (the offeree) with the intention of creating a legally binding agreement. Offers can be categorized into two main types: specific offers and general offers.

Specific Offer:

A specific offer is an offer made to a specific person or group of people. For example, if a person offers to sell their car to a particular individual for a certain price, this is a specific offer. Specific offers can only be accepted by the person or group of people to whom they are addressed. If the offer is not accepted within the specified time period or on the specific terms outlined in the offer, it lapses and cannot be accepted later.

General Offer:

A general offer, on the other hand, is an offer made to the public at large or a group of people who may accept it. For example, an advertisement offering a reward for the return of a lost item is a general offer. Anyone who finds the lost item and meets the conditions of the offer can claim the reward. The key difference between a specific offer and a general offer is that a general offer can be accepted by anyone who meets the conditions of the offer.

Legal Implications:

Specific and general offers have different legal implications. For instance, in the case of a specific offer, the offeror is obligated to sell the item to the offeree if the offeree accepts the offer within the specified time period and on the specific terms outlined in the offer. In the case of a general offer, the offeror is only obligated to fulfill the offer if someone meets the conditions of the offer and accepts it.

Example Case: Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company (1893)

Facts:

One landmark case related to the distinction between specific and general offers is Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company (1893). In this case, the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company made a general offer through newspaper advertisements promising a reward to anyone who used their product and still contracted influenza. The advertisement stated that the company had deposited £1,000 in a bank to show their sincerity in carrying out the offer.

Decision:

Mrs. Carlill purchased and used the product as directed but still contracted influenza. She sued the company for the reward, arguing that she had accepted the general offer by using the product as directed. The company argued that the advertisement was not a specific offer to Mrs. Carlill, and therefore there was no contract between them.

The court ruled in favor of Mrs. Carlill, holding that the advertisement constituted a general offer that she had accepted by using the product as directed. The court held that the advertisement contained specific terms that could be reasonably interpreted as an offer, and that Mrs. Carlill had provided consideration (i.e., using the product as directed) in exchange for the promise of a reward. The court further held that the deposit of £1,000 in a bank demonstrated the company’s intent to be bound by the offer. This case is often cited as a landmark case on the distinction between specific and general offers.

Principle Established:

This case established the principle that a general offer can be accepted by anyone who meets its conditions, creating a binding contract.

Standing, Open, and Continuing Offers

In contract law, offers can be classified into different types based on their duration and ability to be accepted. The three main types of offers are standing offers, open offers, and continuing offers.

Standing Offers

A standing offer is made to a particular person or group of people and is valid for a specific period. It is a type of specific offer that remains open for acceptance during the specified period. For example, if a company offers to sell a particular product to a specific customer at a fixed price for a period of one year, this would be a standing offer.

Key Points:

- Directed at a specific person or group.

- Valid for a specified period.

- Can only be accepted by the designated recipient(s) within the specified period.

Open Offers

An open offer is a type of general offer that is open to anyone who meets the specified conditions. It remains open for a reasonable period and can be accepted by anyone who fulfills the conditions. For example, if a company offers a reward to anyone who returns a lost item, this would be an open offer.

Key Points:

- Open to the public or a general audience.

- Valid for a reasonable period.

- Can be accepted by anyone who meets the specified conditions.

Continuing Offers

A continuing offer remains open for a specified period but can be accepted multiple times during that period. For example, if a company offers to supply a particular product to a customer at a fixed price for one year, and the customer can place orders for the product during that period, this would be a continuing offer.

Key Points:

- Open for a specified period.

- Can be accepted multiple times within the specified period.

- Allows repeated transactions under the same terms.

Legal Implications

The legal implications of these different types of offers can vary:

- Standing Offer: Can only be accepted by the designated person or group within the specified period.

- Open Offer: Can be accepted by anyone who meets the specified conditions within a reasonable period.

- Continuing Offer: Can be accepted multiple times within the specified period, allowing repeated transactions under the same terms.

Understanding these distinctions is important for determining the validity and enforceability of offers in contract law.

Bengal Coal Co. v. Homee Wadia & Co. (1912)

Facts:

The Bengal Coal Co. offered to sell a certain quantity of coal to Homee Wadia & Co., stating that the offer would remain open until a specific date. Homee Wadia & Co. did not accept the offer within the specified time frame but attempted to do so after the date had passed. Bengal Coal Co. refused to accept the order, arguing that the offer had lapsed.

Decision:

The court held that the offer made by Bengal Coal Co. was a standing offer. Since it had not been accepted within the specified time frame, the offer had lapsed. The court emphasized that the nature of a standing offer is such that it can only be accepted within the specified period. Once that period has expired, the offer is no longer valid.

Principle Established:

This case established the principle that a standing offer can only be accepted within the specified period. If the offer is not accepted within that period, it lapses. This case underscores the importance of adhering to the terms and conditions of an offer, which determine its validity.

Rajendra Kumar v. State of Madhya Pradesh (1977)

Facts:

Rajendra Kumar applied for a post in the state government and was selected for the job. He received an appointment letter stating that he had to report for duty within a specified period, failing which his appointment would be cancelled. Rajendra Kumar did not report for duty within the specified period, and his appointment was cancelled.

Rajendra Kumar challenged the cancellation, arguing that the offer made by the state government was a continuing offer, allowing him to report for duty at any time. The state government maintained that the offer was not a continuing offer, and his appointment was rightly cancelled due to his failure to report within the specified period.

Decision:

The court held that the offer made by the state government was not a continuing offer. The applicant was required to report for duty within the specified period. The court stressed that the terms of the offer must be clear and unambiguous, and in this case, the terms explicitly required reporting within a specific timeframe.

Principle Established:

This case established that the doctrine of continuing offers applies only when the offer is clear and unambiguous, with terms that provide for ongoing acceptance. It highlights the significance of the terms and conditions of an offer in determining its validity.

Key Takeaways:

- Standing Offers: Must be accepted within the specified period, as demonstrated in Bengal Coal Co. v. Homee Wadia & Co.

- Continuing Offers: Only valid if the terms are clear and allow for ongoing acceptance, as clarified in Rajendra Kumar v. State of Madhya Pradesh.

These cases illustrate the importance of the specific terms and conditions of an offer in contract law, affecting how and when an offer can be validly accepted.

Comment

Nothing for now