Acceptance under Indian Contract Act 1872

According to the Indian Contract Act 1872, acceptance is the final and unqualified expression of assent to the terms of a proposal. Acceptance must be given in the manner and within the time specified in the proposal, or if no time is specified, within a reasonable time.

Definition of Acceptance (Section 2(b))

“When the person to whom the proposal is made signifies his assent thereto, the proposal is said to be accepted. A proposal, when accepted, becomes a promise.”

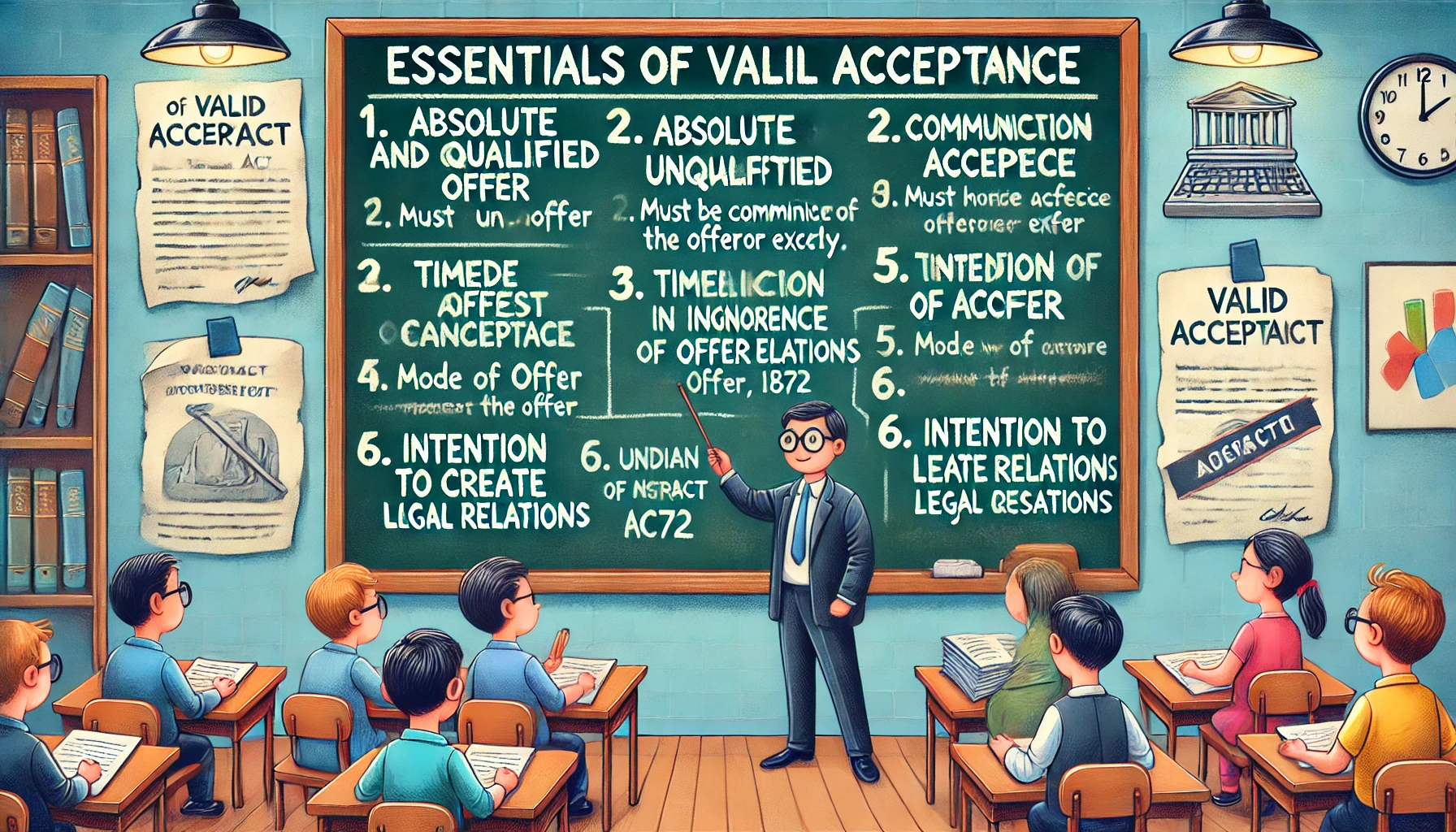

Valid Acceptance Criteria

- Given by the Person to Whom the Proposal is Made: The acceptance must be made by the person to whom the proposal was addressed.

- Given in the Manner Prescribed: Acceptance must follow the manner specified by the proposer.

- Given within the Time Prescribed: Acceptance must be communicated within the time specified in the proposal or within a reasonable time.

- Absolute and Unqualified: The acceptance must be unconditional and unequivocal.

If acceptance is not given in the prescribed manner or within the prescribed time, it is considered invalid, and the proposer is no longer bound by the proposal.

Types of Acceptance

- Express Acceptance: Given through words or writing.

- Implied Acceptance: Given through the conduct of the offeree.

Communication of Acceptance

"Acceptance must be communicated" is a fundamental principle of contract law. For a contract to be legally binding, the acceptance of a proposal or offer by the offeree must be communicated to the proposer or offeror.

- Communication Methods: Acceptance can be communicated through any reasonable means, such as writing, orally, or through conduct.

- Timing and Conditions: The communication must be made within a reasonable time and must be absolute and unconditional.

Failure to communicate acceptance means no contract is formed, and the offeror is not bound by the offer. Therefore, it is essential for the offeree to communicate their acceptance within a reasonable time to form a legally binding contract.

Landmark Case Law

Felthouse v Bindley

Paul Felthouse, the complainant, discussed buying a horse from his nephew, John Felthouse. After their conversation, Paul wrote a letter to his nephew stating that if he did not hear anything further regarding the horse, he would consider the purchase agreed upon and would own the horse. John did not reply to this letter and was busy with auctions. The defendant, Mr. Bindley, was running the auctions, and John instructed him not to sell the horse. However, Mr. Bindley accidentally sold the horse to someone else.

Issues: Paul Felthouse sued Mr. Bindley for the tort of conversion, which required him to prove that the horse was his property and that a valid contract existed. The central issue was whether silence or failure to reject an offer could constitute acceptance.

Decision / Outcome: The court held that there was no contract for the horse between Paul Felthouse and his nephew. The court ruled that silence did not amount to acceptance, and an obligation cannot be imposed on someone by another person. Acceptance of an offer must be clearly communicated. Despite the nephew's intention to sell the horse to Paul and the nephew's interest in the sale, there was no binding contract because the nephew did not explicitly accept the offer. Therefore, the nephew's failure to respond did not constitute acceptance of the offer.

Case Study: Mr. Powell's Appointment as Headmaster

Facts: Mr. Powell, the plaintiff, was a candidate for the position of headmaster at a school. The manager referred his candidature to the appointing authority, which subsequently passed a resolution to appoint him to the position. However, no formal acceptance was communicated directly to Powell; these were internal discussions only. A board member overheard the discussion where other members talked about appointing Powell as the headmaster and informed Powell of this. Powell was pleased with the news, but later, the board members decided to cancel the resolution appointing him. Consequently, Powell filed a suit against the managers for breach of contract.

Issues: The primary issue before the court was whether there was an actual breach of contract as claimed by the plaintiff.

Judgement: The court ruled that there was no breach of contract because the acceptance of Powell's appointment was never formally conveyed to him. The court noted that for a valid acceptance to constitute a contract, it must be communicated by an authorized person to the plaintiff. In the absence of such communication, a valid contract could not be formed. Thus, the court held that a contract was never established in this case.

Acceptance by Conduct

Acceptance by conduct occurs when a contract is formed through the actions or behavior of the parties rather than explicit communication. This type of acceptance, also known as acceptance by performance or behavior, does not require the offeree to communicate acceptance explicitly. Instead, the offeror infers acceptance from the offeree's actions.

Example: If someone orders a product online and the seller delivers the product without receiving explicit acceptance, the buyer's acceptance of the product constitutes acceptance by conduct. The buyer's actions align with the terms of the offer, indicating acceptance.

For acceptance by conduct to be valid, the offeree's actions must clearly align with the offer's terms, and the offer must not require explicit communication of acceptance. An example of this can be seen in the case of Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company, where the plaintiff's use of the smoke ball as directed was considered acceptance of the company's offer, forming a contract.

When Communication is Complete

- As against the proposer (offeror): Communication is complete when the acceptance is put into transmission so that it is out of the offeree's control. This means that if the offeree sends the acceptance via post or other authorized means, the communication is considered complete once it is posted.

- As against the acceptor (offeree): Communication is complete when the offeror becomes aware of the acceptance. This can happen if the acceptance is directly communicated by the offeree or through a messenger.

- When transmitted through authorized means: If the acceptance is sent through a recognized and authorized means (such as postal service, telegraph, or fax), communication is considered complete when the message is transmitted.

Acceptance by Post

Acceptance by post is a commonly used method in contract law, based on the principle that communication is complete when the acceptance is put in the course of transmission. According to Section 4 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, if the offeree accepts the offer by post, the communication of acceptance is considered complete as soon as the acceptance is posted. This rule applies even if the acceptance is lost, delayed, or damaged in transit, provided it is properly addressed, stamped, and posted.

Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Company v Grant

In this case, Mr. Grant applied for a fire insurance policy from the Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Company. The company sent him a policy document, which he received on November 23, 1877. The document stated that the policy would be effective only upon payment of the first premium. Mr. Grant did not pay the premium but instead sent a letter on December 23, 1877, accepting the policy.

The company argued that Mr. Grant's acceptance was invalid as it was not communicated in the specified manner (i.e., by paying the premium). They claimed the policy document was an offer, and Mr. Grant's letter was a counter-offer, which had not been accepted.

Judgement: The court held that Mr. Grant's letter constituted a valid acceptance, effective upon posting, per the postal rule. The court determined that acceptance by post is effective as soon as it is posted, regardless of when it is received, or even if it is lost. This case established the postal rule principle, emphasizing the importance of clear communication and the specified manner of acceptance.

Adams v Lindsell

In this case, Lindsell offered to sell a quantity of wool to Adams, with the offer made on September 2nd. Due to an addressing error, the offer reached Adams on September 5th, who accepted it on the same day by post. However, due to postal delays, Lindsell received the acceptance on September 9th, after selling the wool to someone else.

Decision: Adams sued for breach of contract, but Lindsell argued that no contract was formed since the acceptance arrived after the offer had been revoked. The court ruled that the contract was formed when the acceptance was posted, not when it was received. This case reinforced the postal rule, establishing that acceptance is effective upon posting when using a reasonable means of communication like the postal service.

Place of Acceptance

The place of acceptance refers to the location where the offeree communicates acceptance to the offeror. This location determines the jurisdiction and applicable law for the contract. In the case of acceptance by post, the place of acceptance is where the acceptance is posted. For telephone or telex communications, acceptance is complete when the offeror receives the acceptance message, making the place of acceptance the location of the offeror.

Acceptance by Telephone or Telex

In cases of acceptance by telephone or telex, acceptance is not complete until the offeror receives the acceptance message. The place of contract formation is the location of the offeror. This differs from the postal rule, where acceptance is effective upon posting.

Case Example: Bhagwan Das v Girdgari Lal

In this case, the plaintiff offered to sell a house to the defendant, who accepted the offer by telephone. Later, the defendant refused to complete the transaction, arguing the acceptance was invalid as it was not in writing. The court held that telephone acceptance was valid, noting that the essential requirement for acceptance was communication to the offeror. The absence of a written confirmation did not invalidate the acceptance, as the defendant had not requested it.

Acceptance Must Be Absolute and Unqualified

For acceptance to be valid, the offeree must accept all terms of the offer without modifications, conditions, or qualifications. Any attempt to change the offer terms constitutes a counter-offer, not acceptance, preventing a binding contract from forming. This principle was illustrated in Hyde v. Wrench, where the plaintiff's counter-offer nullified the original offer, preventing a contract from forming when the plaintiff later tried to accept the original terms.

Acceptance Must Be in the Manner Prescribed by the Proposer

Under the Indian Contract Act, if the proposer specifies a particular manner for acceptance, it must be followed. This ensures clarity in how acceptance should be communicated. If the proposer specifies acceptance by email or fax, for example, then the offeree must use that method. Failure to comply with the specified manner results in invalid acceptance, preventing a contract from forming.

Share

Related Post

Tags

Archive

Popular & Recent Post

Comment

Nothing for now