Personal laws refer to laws that are specific to a particular religion and govern matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, and family relationships. These laws are deeply rooted in the traditions, customs, and beliefs of each religion and have evolved over time to adapt to changing social norms.

1. Definition of Personal Laws

- Personal laws are a set of rules that apply based on religion and cultural practices.

- They regulate private matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, property rights, and adoption.

2. Basis of Personal Laws

- Derived from ancient customs, scriptures, or religious teachings.

- Serve as the legal framework for maintaining harmony in religious and community practices.

3. Examples of Personal Laws

- Hindu Law:

- Governed by the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, and Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956.

- Addresses issues like intestate succession (inheritance without a will), divorce, and adoption.

- Women were given equal rights to property after the 2005 amendment.

- Muslim Law:

- Governed by the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937.

- Based on the Quran and interpretations under Shia and Sunni schools.

- Does not recognize adoption like Hindu law but allows guardianship.

4. Key Features of Personal Laws

- Respect for Religious Sentiments: Designed to reflect the beliefs and traditions of the community.

- Customized for Each Religion:

- Hindu law allows adoption and recognizes ancestral property.

- Muslim law emphasizes joint property and inheritance under Shariat law.

- Evolved Over Time: Amendments have been made to ensure equality and modern relevance, such as equal property rights for women in Hindu law.

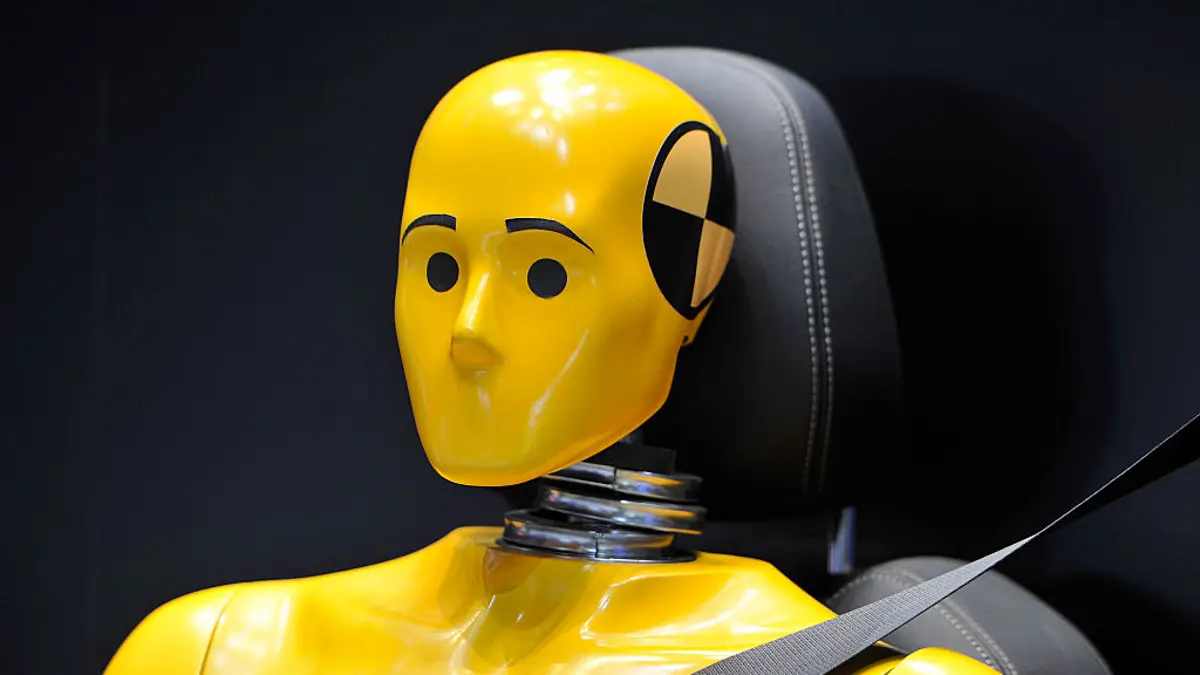

5. Challenges with Personal Laws

- Complexity: Different laws for different religions make legal processes complicated.

- Gender Inequality: Historically, some personal laws have been criticized for favoring men (e.g., unequal inheritance rights for women).

- Secularism: Critics argue for a uniform set of laws for all citizens to ensure equality.

6. Need for Uniform Civil Code (UCC)

- Article 44 of the Indian Constitution calls for a Uniform Civil Code.

- UCC would provide a common set of laws for all citizens, regardless of religion, ensuring equality and simplicity.

7. Conclusion

Personal laws are essential for respecting religious diversity in a country like India. However, they can create legal complexities and inconsistencies. Moving towards a Uniform Civil Code could simplify these laws and promote equality among all citizens, emphasizing that we are Indians first.

1. Concept of Personal Laws

- Definition: Personal laws are specific to each religion and help regulate relationships in families and communities.

-

Examples:

- Hindu laws like the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, and Hindu Succession Act, 1956.

- Muslim laws like the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937.

- Significance: These laws respect the religious beliefs and traditions of each community while also adapting to modern changes, like giving women equal property rights.

2. Types of Families

A. Based on Lineage (Who Inherits Property and Family Name):

-

1. Matrilineal Families:

- Definition: Lineage and inheritance are traced through the mother’s side.

- Characteristics:

- Property passes from mother to daughter.

- Children belong to the mother’s family.

- Example: Found in certain communities in Kerala, like the Nairs and Khasi tribes of Meghalaya.

-

2. Patrilineal Families:

- Definition: Lineage and inheritance are traced through the father’s side.

- Characteristics:

- Property is passed from father to son.

- Children belong to the father’s family.

- Example: Common in most Indian societies.

B. Based on Residence (Where the Family Lives After Marriage):

-

1. Matrilocal Families:

- Definition: The husband moves to the wife’s family after marriage.

- Characteristics:

- The wife’s family provides residence and support.

- Often linked to matrilineal systems.

- Example: Practiced by some tribal communities in Northeast India.

-

2. Patrilocal Families:

- Definition: The wife moves to the husband’s family after marriage.

- Characteristics:

- The husband’s family provides residence and support.

- Often linked to patrilineal systems.

- Example: Common in Hindu and Muslim families in India.

C. Based on Authority (Who Has Decision-Making Power):

-

1. Matriarchal Families:

- Definition: The mother or eldest female is the head of the family.

- Characteristics:

- Women control property and family decisions.

- Rare in most societies but present in matrilineal communities.

- Example: Khasi and Garo tribes in Meghalaya.

-

2. Patriarchal Families:

- Definition: The father or eldest male is the head of the family.

- Characteristics:

- Men make most family decisions.

- Common in most Indian families.

- Example: Typical in Hindu, Muslim, and other patriarchal societies.

1. Hindu Law

Hindu law is one of the oldest legal systems in the world and is rooted in the concept of Dharma. It governs the lifestyle, customs, and duties of Hindus. The laws were originally based on religious texts and practices.

Origin of Hindu Law

- Based on Dharma:

- Dharma represents the way of life for Hindus, covering every aspect from birth to death.

- Kings in ancient times governed based on Dharma, ensuring laws aligned with it.

- Customs and Practices:

- Hindu law evolved from the customs followed by people over time.

Sources of Hindu Law

Sources are divided into two categories: Ancient Sources and Modern Sources.

A. Ancient Sources

- Shruti (What is Heard):

- Derived from the word "Shur," meaning to hear.

- Refers to the four Vedas: Rigveda, Samveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda.

- These texts were recited by Brahmins, considered knowledgeable, and formed the foundation of Hindu law.

- Smriti (What is Remembered):

- Derived from "Smri," meaning to remember.

- Smritis were written by sages based on the Shrutis.

- Two main types:

- Dharmasastras: Focused on moral conduct.

- Dharmasutras: Covered government, caste, economic affairs, and social relationships.

- Famous examples: Manusmriti (first law book) and Yajnavalkya Smriti.

- Digests and Commentaries:

- Written by scholars to explain and interpret Smritis.

- Examples:

- On Manusmriti: Manubhasya by Medhatithi.

- On Yajnavalkya Smriti: Mitakshara by Vigneshwara.

- Customs:

- Traditions practiced over generations and accepted as law.

- Recognized by courts if they are valid, continuous, widely followed, and not harmful to society.

- Types of customs:

- Local customs: Specific to a region.

- Class customs: Followed by a specific group.

- Family customs: Binding on family members.

B. Modern Sources

- Justice, Equity, and Good Conscience:

- Judges used fair judgment in cases without existing laws.

- Based on fair play and justice but lacked uniformity.

- Legislation:

- Acts passed by Parliament codifying Hindu laws.

- Examples:

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955.

- Hindu Succession Act, 1956.

- Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956.

- Precedents:

- Courts follow decisions made in earlier cases to ensure consistency.

- Supreme Court decisions are binding on lower courts.

Schools of Hindu Law

- 1. Mitakshara School:

- Based on the commentary by Vigneshwara on Yajnavalkya Smriti.

- Focuses on rituals, marriages, and rites of pregnancy.

- Sub-schools:

- Banaras School: Northern India.

- Mithila School: Bihar.

- Bombay School: Gujarat and Maharashtra.

- Madras School: Southern India.

- 2. Dayabhaga School:

- Focused on Bengal and Assam.

- Emphasizes logic and reason over customs.

- Broadened the list of heirs in inheritance laws.

2. Muslim Law

Muslim law is rooted in the teachings of the Quran and Sunnah and governs the lives of Muslims in matters like marriage, divorce, and inheritance.

Origin of Muslim Law

- Divine Origin:

- Based on Allah’s commands revealed to Prophet Muhammad.

- Developed Through Practices:

- Includes traditions and customs adapted to evolving societal norms.

Sources of Muslim Law

Sources are divided into Primary Sources and Secondary Sources.

A. Primary Sources

- Quran:

- Holy book containing Allah’s commands.

- Covers rules for personal conduct, family matters, and social behavior.

- Sunnah:

- Refers to the practices and sayings of Prophet Muhammad.

- Acts as a guide when the Quran is silent on an issue.

B. Secondary Sources

- Ijma (Consensus):

- Agreement among Islamic jurists on a legal issue.

- Sunni jurists consider it a primary source, while Shia jurists see it as secondary.

- Qiyas (Analogical Deduction):

- Applying reasoning to solve new issues by drawing analogies with existing rules in the Quran and Sunnah.

Schools of Muslim Law

- 1. Hanafi School:

- Most liberal and widely followed in North India.

- Focuses on rational deduction.

- 2. Maliki School:

- Followed in parts of Africa and the Middle East.

- Gives importance to practices in Medina, where Prophet Muhammad lived.

- 3. Hanbali School:

- Orthodox and strict in following the Quran and Sunnah.

- Liberal in trade-related matters.

- 4. Shafi School:

- Followed in Yemen, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia.

- Relies on Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas but uses Qiyas less frequently.

Conclusion

Hindu and Muslim laws have evolved from religious texts, customs, and practices. They have been shaped over centuries by scholars, judges, and legislative bodies. Understanding their origins, sources, and schools helps highlight the richness and diversity of India’s legal system.

1. Shia Law

- Origin:

- Derived from the followers of Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of Prophet Muhammad.

- Shia Muslims believe that leadership (Imamat) should remain within the Prophet’s family.

- Sources:

- Primary: Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and reason (Aql).

- Unique Features:

- Greater reliance on reasoning (Ijtihad).

- Limited acceptance of Ijma (consensus) unless by specific Imams.

- Key Schools:

- Imamiyah (Twelvers): Most prominent, based on 12 Imams.

- Ismaili (Seveners): Recognize seven Imams.

- Zaidi (Fivers): Follow five Imams, closer to Sunni practices.

2. Sunni Law

- Origin:

- Sunni Muslims believe in the selection of Caliphs through consensus rather than family lineage.

- They follow the sayings and actions of Prophet Muhammad and his companions.

- Sources:

- Primary: Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas (analogical deduction).

- Unique Features:

- Emphasis on Ijma as a significant source of law.

- Greater reliance on Qiyas (analogical reasoning).

- Key Schools:

- Hanafi: Liberal, emphasizes reasoning and equity.

- Maliki: Values the practices of Medina's people during Prophet Muhammad's time.

- Shafi: Focuses on Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas but uses Qiyas conservatively.

- Hanbali: Strict, emphasizes Quran and Sunnah over analogical reasoning.

Key Differences Between Shia and Sunni Law

| Aspect | Shia Law | Sunni Law |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership | Belief in Imams as divinely appointed leaders. | Leadership by consensus (Caliphate). |

| Sources of Law | Quran, Sunnah, Ijma (by Imams), Aql (reason). | Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas (analogical deduction). |

| View on Ijma | Limited to the decisions of Imams. | Broader consensus among jurists. |

| Role of Reasoning | High reliance on reasoning (Ijtihad). | Reasoning is secondary to Quran and Sunnah. |

| Marriage Laws | Temporary Marriage (Mutah) is allowed. | Temporary marriage is not allowed. |

| Inheritance | Females may receive a fixed share depending on the Imam's ruling. | Clear division according to Quranic guidelines. |

| Prayer Practices | Combine prayers (e.g., Zuhr and Asr together). | Perform five separate prayers daily. |

| Legal Interpretation | Dynamic, depends heavily on Imam’s interpretation. | Conservative, follows traditional methods. |

Conclusion

While both Shia and Sunni laws derive their principles from the Quran and Sunnah, they differ in interpretation, sources, and practices. These differences reflect their unique historical development and cultural influences. Understanding these distinctions is vital for comprehending the diversity within Islamic law.

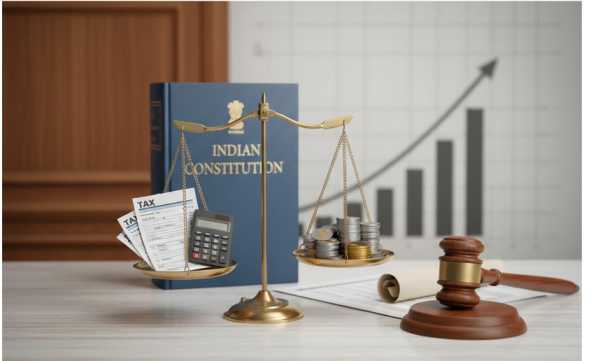

1. Understanding Article 44 of the Indian Constitution

- Directive Principle of State Policy:

- Article 44 states that the state shall strive to implement a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) across India.

- This aims to replace personal laws based on religion with a common set of rules governing personal matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, and adoption.

- Not Enforceable by Law:

- As a Directive Principle, it is not a binding legal provision but a guideline for the government to work towards.

2. The Need for Uniform Civil Code

- Equality Under the Law:

- Aims to provide equal rights and eliminate discrimination based on religion or gender.

- Gender Justice:

- Addresses issues like unequal inheritance rights, triple talaq, and child marriage, ensuring fairness for women.

- National Integration:

- Promotes a unified legal framework to foster national unity and reduce divisions based on religious laws.

- Simplification of Laws:

- Reduces complexity by replacing multiple personal laws with a single set of rules.

3. Drafting a Uniform Civil Code

- Key Areas Covered:

- Marriage and Divorce: Common age of marriage, equal grounds for divorce.

- Inheritance and Succession: Equal property rights for men and women.

- Adoption: Uniform guidelines for adoption across all communities.

- Guardianship: Equal rights for parents in child custody matters.

- Proposed Features of the Draft UCC:

- Gender Neutrality: Eliminates biases against women in personal laws.

- Religious Neutrality: Ensures that no community’s beliefs dominate others.

- Human Rights Alignment: Incorporates principles of equality and dignity from international human rights standards.

4. Judicial Pronouncements Supporting UCC

- Shah Bano Case (1985):

- Emphasized the need for UCC to uphold women's rights and national integration.

- Sarla Mudgal Case (1995):

- Urged the government to expedite UCC implementation.

- Shayara Bano Case (2017):

- Abolished triple talaq, reigniting discussions about UCC.

5. Arguments in Favor of UCC

- Promoting Equality:

- Eliminates discrimination in personal laws.

- Ensures equal treatment for men and women, irrespective of religion.

- Empowering Women:

- Corrects gender biases like unequal inheritance and child marriage.

- Streamlining Legal Processes:

- Simplifies the legal system, reducing court backlog and disputes.

- National Unity:

- Prioritizes citizenship over religious identity in legal matters.

- Social Modernization:

- Aligns personal laws with contemporary values, including LGBTQ+ rights.

Conclusion

The Uniform Civil Code is a complex yet essential step towards equality and national integration. While Article 44 envisions a common legal framework, its implementation requires careful consideration of cultural diversity and minority rights. A gradual, inclusive approach can pave the way for a UCC that upholds justice, equality, and social harmony in India.

1. Hindu Marriage Law

- Definition:

- In Hindu law, marriage is considered a sacrament rather than a contract.

- It is a religious duty and one of the 16 samskaras (rites of passage).

- The purpose of Hindu marriage is spiritual union, social cooperation, and procreation.

- Legal Framework:

- Governed by the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955.

- Includes Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists under its ambit (Article 25(2)(b) of the Constitution).

- Key Points:

- Marriage must comply with specific conditions under Section 5 of the Act, such as no existing spouse, sound mind, legal age (21 for men, 18 for women), and absence of prohibited relationships.

- Saptapadi (Seven Steps): A vital ritual where the couple walks seven steps around the sacred fire, marking the binding authority of the marriage.

2. Muslim Marriage Law

- Definition:

- In Muslim law, marriage is a civil contract (Nikahnama), not a sacrament.

- It is a mutual agreement between a man and a woman to live together as husband and wife.

- Legal Framework:

- No codified law governs Muslim marriages; it is based on the Shariat and personal laws.

- Key Points:

- Essential requirements include:

- Ijab (Proposal) and Qubool (Acceptance).

- Mehr (Dower) as consideration for the marriage.

- Free consent of both parties.

- Presence of witnesses (number varies for Shia and Sunni sects).

- Types of Marriages: Sahih (Valid), Fasid (Irregular), and Batil (Void).

- Muta Marriages: Temporary and pleasure-based marriages recognized by Shia Muslims but not Sunni Muslims.

- Essential requirements include:

3. Christian Marriage Law

- Definition:

- Marriage in Christian law is a sacred union performed under religious and civil regulations.

- Legal Framework:

- Governed by the Indian Christian Marriage Act, 1872.

- Includes marriage between Christians and between a Christian and non-Christian (with specific provisions).

- Key Points:

- Marriage must be solemnized by an authorized priest or Marriage Registrar.

- Conditions include:

- Minimum age (21 for men, 18 for women).

- Consent of both parties.

- No existing spouse at the time of marriage.

Conclusion

Marriage is a universal institution, but its definition and interpretation vary across religions in India. While Hindu and Christian laws view marriage as a sacred union, Muslim law considers it a civil contract. The Special Marriage Act provides a secular framework for interfaith and inter-caste marriages. The demand for inclusivity, such as recognizing LGBTQIA+ marriages, highlights the need to update and harmonize marriage laws to reflect modern societal values.

1. Both Parties Must Be Hindus

- Requirement: Both individuals must be Hindus at the time of marriage.

- Legal Basis: Section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act.

- Explanation: If one party follows a different religion, the marriage is not valid under this Act.

- Case Law: In Yamunabai Anant Rao Adhav v. Anant Rao Shivaram Adhav (1988), the Supreme Court ruled that a marriage between a Hindu and a Christian was void under this Act.

2. Soundness of Mind and Legal Consent

- Requirement:

- Both parties must be capable of giving legal consent.

- Neither party should suffer from unsoundness of mind, mental disorder, or insanity.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(ii) of the Act.

- Key Points:

- If a party is incapable of giving consent or has a mental condition that makes them unfit for marriage or bearing children, the marriage can be annulled.

- Case Law: In Alka Sharma v. Chandra Sharma (1991), the court annulled a marriage where the woman exhibited irrational behavior, making her unfit for marital life.

3. Monogamy

- Requirement: Neither party should have a living spouse at the time of marriage.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(i) and Section 17 of the Act.

- Key Points:

- Second marriages are void unless the first marriage has ended due to death or divorce.

- Penalties for bigamy include imprisonment and fines under Sections 494 and 495 of the Indian Penal Code.

4. Age Requirements

- Requirement:

- The bride must be at least 18 years old, and the groom must be at least 21 years old.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(iii) of the Act.

- Key Points:

- Marriages that violate age requirements are not void but are punishable under Section 18 of the Act with imprisonment, fines, or both.

- Case Law: In P. Venkataramana v. State (1977), it was held that violation of age requirements does not invalidate the marriage but is punishable.

5. Prohibition of Sapinda Relationships

- Requirement: Marriage within Sapinda relationships is prohibited unless allowed by custom.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(v) and Section 3(f) of the Act.

- Key Points:

- Sapinda relationships extend up to three generations on the mother’s side and five generations on the father’s side.

- Violations are punishable with imprisonment or fines under Section 18.

6. Prohibited Degrees of Relationship

- Requirement: Marriage between individuals within prohibited degrees of relationship is not allowed unless custom permits.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(iv) and Section 3(g) of the Act.

- Key Points:

- Prohibited relationships include close family members like siblings, ascendants, and descendants.

- Case Law: In Balu Swami Reddiar v. Balakrishna (1956), the court declared a marriage void as it violated the prohibition on close familial connections.

7. Solemnisation of Marriage According to Customary Rites

- Requirement: Marriage must be solemnised according to the customary rites and ceremonies of either party.

- Legal Basis: Section 7 of the Act.

- Key Points:

- The Saptapadi (Seven Steps) ritual is essential, and the marriage is considered complete when the seventh step is taken.

- Case Law: In Bibba v. Ramkall (1982), the court emphasized the need for proper ceremonial rites to validate the marriage.

1. Recognized Forms (Valid)

- Brahma Marriage: The bride’s father gives her as a gift to a groom with good character.

- Daiva Marriage: The bride is given to a priest performing a religious ritual.

- Arsha Marriage: The groom gives symbolic gifts like cows to the bride’s father.

- Prajapatya Marriage: Marriage for fulfilling familial and societal duties.

2. Unrecognized or Invalid Forms

- Asura Marriage: The bride is given in exchange for money or gifts.

- Gandharva Marriage: Marriage based solely on mutual love and consent without rituals.

- Rakshasa Marriage: Marriage by force or abduction.

- Paisacha Marriage: The bride is married without her consent, often in a vulnerable state.

Conclusion

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, ensures that marriages follow essential conditions for validity, including mutual consent, legal age, and adherence to traditional rites. Understanding traditional categories helps appreciate the evolution of Hindu marriage practices.

1. Proposal and Acceptance (Ijab and Qubul)

- Requirement:

- There must be an offer (Ijab) by one party and acceptance (Qubul) by the other.

- Both must occur in the same meeting.

- Importance: A delayed or deferred acceptance invalidates the marriage.

2. Competency of Parties

- Legal Age:

- Puberty is considered the age of legal marriage, generally presumed at 15 years unless proven otherwise.

- Case Law: In Muhammad Ibrahim v. Atkia Begum, it was held that puberty is reached at 15 years unless earlier maturity is proven.

- Guardians for Minors:

- If a party is below the age of puberty, the guardian's consent is necessary.

- Guardians include the father, paternal grandfather, mother, or other male family members.

- Sound Mind: Both parties must be mentally capable of understanding the contract. A lunatic can marry during periods of sanity.

- Muslim Faith: Both parties must be Muslims. Inter-sect marriages are allowed, e.g., between Sunni and Shia Muslims.

3. Free Consent

- Requirement: Consent must be free and voluntary. Coercion, fraud, or mistake of fact makes the marriage void.

- Case Law: In Mohiuddin v. Khatijabibi, the court ruled that free consent is a cornerstone of a valid Muslim marriage.

4. Dower (Mahr)

- Definition: A monetary or property consideration given by the groom to the bride.

- Purpose: Ensures financial security for the bride.

- Case Law: In Nasra Begum v. Rizwan Ali, the court held that dower must be settled before cohabitation.

5. Freedom from Legal Disability

- Absolute Prohibitions (Void Marriage):

- Consanguinity: Prohibition on marrying close blood relatives.

- Affinity: Prohibition on marrying close relatives by marriage.

- Fosterage: Prohibition on marrying foster relatives.

- Relative Prohibitions (Irregular Marriage):

- Unlawful Conjunction: Marrying two closely related women at the same time.

- Polygamy: Marrying more than four wives simultaneously.

- Witness Absence: Sunni law requires witnesses.

- Marriage During Iddat: Waiting period after divorce or husband’s death.

6. Registration of Muslim Marriages

- Not Mandatory: Islamic law does not require registration.

- Encouraged: Registration provides legal documentation.

- Case Law: In Seema v. Ashwani Kumar, the Supreme Court emphasized registering all marriages to ensure legal proof.

1. Valid Marriage (Sahih)

- Definition: Fulfills all legal and religious requirements.

- Key Features:

- Free consent.

- Competent parties.

- Absence of prohibitions.

2. Void Marriage (Batil)

- Definition: Does not meet essential conditions.

- Examples:

- Marriage within prohibited degrees of consanguinity or fosterage.

- Marrying someone already married under Shia law.

- Consequence: Void ab initio (from the beginning).

3. Irregular Marriage (Fasid)

- Definition: Violates relative prohibitions but can be rectified.

- Examples:

- Marriage without witnesses (in Sunni law).

- Marriage during the Iddat period.

- Fifth marriage while four wives are still alive.

- Consequence: Becomes valid after rectifying irregularities.

Special Types of Marriages

1. Muta Marriage (Temporary Marriage)

- Definition: A temporary marriage for a fixed period and specific consideration.

- Key Features:

- Not practiced by Sunni Muslims.

- Practiced by Shia Muslims.

- Ends when the stipulated period expires.

2. Nikah Halala

- Definition: A practice where a divorced woman marries another man and then divorces him to remarry her first husband.

- Purpose: Observed under specific interpretations of Sharia law after a triple talaq.

- Controversy: Widely criticized for being exploitative and against women's rights.

Conclusion

Muslim marriage is a deeply significant institution governed by specific legal and religious rules. Essentials like free consent, competency, and adherence to prohibitions ensure the sanctity of the union. While valid marriages reflect adherence to Islamic law, void and irregular marriages demonstrate the consequences of deviation from these principles. Special types like Muta marriages and Nikah Halala add complexity to Islamic matrimonial laws, highlighting the need for understanding and reform in contemporary times.

Key Features of Solemnisation under the Act

1. Applicability

- The Act applies to all individuals in India regardless of their religion (Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, or any other religion).

- It is also applicable to Indian citizens living abroad.

2. Conditions for a Valid Marriage

- Non-Existence of a Living Spouse: Neither party should have an existing living spouse at the time of marriage.

- Capacity to Consent: Both parties must be capable of giving free and informed consent. They should not be suffering from any mental illness that makes them unfit for marriage or procreation.

- Age Requirements: The male must be at least 21 years old, and the female must be at least 18 years old.

- Prohibited Relationships: The parties should not fall within degrees of prohibited relationships unless their customs allow such unions.

3. Notice of Intended Marriage

- Parties intending to marry must give a written notice to the Marriage Officer in the district where at least one of them has resided for 30 days prior.

- The notice includes:

- Names, ages, and addresses of the parties.

- A declaration that they fulfill the conditions of marriage.

4. Public Notice and Objections

- Public Notice: The Marriage Officer displays the notice in a conspicuous place in his office for 30 days to invite objections, if any.

- Objections to Marriage:

- Any person can object to the marriage within the 30-day period on legal grounds (e.g., failure to meet age requirements, prohibited relationships).

- The Marriage Officer investigates the objection and decides accordingly.

5. Solemnisation of Marriage

- After the 30-Day Period: If no objections are raised or resolved, the marriage can be solemnised.

- Presence of Witnesses: The marriage must take place in the presence of the Marriage Officer and three witnesses.

- Declaration of Consent:

- Both parties must declare their consent by saying: "I, [Name], take thee, [Name], to be my lawful wife/husband."

- This declaration must be made in the presence of the witnesses and the Marriage Officer.

- Certificate of Marriage: Upon completion of the ceremony, a Certificate of Marriage is issued, signed by the parties, witnesses, and the Marriage Officer. This certificate is the conclusive proof of the marriage.

6. Non-Compliance

- Failure to comply with the conditions or procedures under the Act renders the marriage invalid.

Significance of the Special Marriage Act

- Secular Nature: Provides a neutral framework for inter-religious and inter-caste marriages.

- Legal Protection: Offers legal recognition and safeguards to the marital relationship.

- Inclusivity: Ensures rights and legitimacy for couples irrespective of their faith or cultural practices.

- Alternative to Personal Laws: Allows individuals who wish to avoid traditional personal laws to marry under a secular legal framework.

Conclusion

The Special Marriage Act, 1954, is a progressive law that facilitates interfaith and intercaste unions by offering a secular and inclusive framework. Its systematic procedure for solemnisation and registration ensures legal validity and protection for marriages that might otherwise face societal or legal challenges under personal laws.

Observations of the Supreme Court

- Constitutional Validity:

- A five-judge Constitution Bench ruled (3:2 verdict) against giving constitutional validity to same-sex marriages.

- The court stated that same-sex marriage is not a fundamental right under the Constitution.

- Parliament's Domain: The Supreme Court emphasized that the Special Marriage Act (SMA), 1954 cannot be modified by the judiciary to include same-sex marriages and left the formulation of such laws to the Parliament and state legislatures.

- Queer Relationships: The court acknowledged the right of queer persons to form unions and recognized the evolving nature of marriage, but reiterated that there is no fundamental right to marry under the Constitution.

- Civil Unions: The Chief Justice of India and Justice Kaul favored recognizing civil unions for same-sex couples, granting specific rights akin to marriage without personal law recognition.

Legality of Same-Sex Marriages in India

- Not a Fundamental Right:

- The right to marry is not explicitly recognized as a fundamental right in the Indian Constitution.

- It is treated as a statutory right regulated by various marriage laws like the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, and the SMA, 1954.

- Judicial Observations on Marriage:

- Shafin Jahan Case (2018): SC held that the right to marry a person of one’s choice is integral to Article 21 (Right to Life and Liberty).

- Navtej Singh Johar Case (2018): SC decriminalized homosexuality, stating that LGBTQIA+ individuals are entitled to equal protection under the law.

Key Features of the Special Marriage Act (SMA), 1954

- Secular Framework: Provides civil marriage rights irrespective of religion, caste, or faith, and is not governed by personal laws.

- Interfaith and Intercaste Marriages: Allows individuals from different religious and social backgrounds to marry legally.

- Exclusions: Currently does not include same-sex couples under its ambit.

Arguments in Favor of Legalizing Same-Sex Marriages

- Equal Rights: Denying same-sex couples the right to marry violates Article 14 (Equality before the law).

- Recognition of Relationships: Legalizing same-sex marriage would provide social and economic benefits like inheritance, tax benefits, and medical decisions.

- Fundamental Right to Happiness: Marriage as a pursuit of happiness is a core principle under Article 21.

- Global Precedents: Same-sex marriage is legal in 32 countries globally; India must align with international human rights norms.

- Biological and Gender Equality: The SC has observed that gender is not binary and biological distinctions are not absolute.

Arguments Against Legalizing Same-Sex Marriages

- Cultural and Religious Concerns: Many traditional and religious groups oppose same-sex marriages, citing violation of their beliefs.

- Purpose of Marriage: Critics argue that the biological purpose of marriage is procreation, which is not possible in same-sex unions.

- Legal Challenges: Recognizing same-sex marriages would require substantial changes in inheritance, property rights, and family laws.

- Child Adoption Concerns: Adoption by queer couples may lead to social stigma and psychological challenges for children in Indian society.

Way Forward

- Awareness Campaigns: Promote equality and acceptance of the LGBTQIA+ community through public awareness programs.

- Amendments in SMA: Amend the Special Marriage Act, 1954 to include same-sex couples, providing them legal marriage rights.

- Civil Unions: Introduce provisions for civil unions to grant same-sex couples legal and economic benefits without redefining "marriage."

- Engage with Stakeholders: Facilitate dialogue with religious leaders and communities to bridge the gap between traditional values and modern legal frameworks.

- Judicial and Legislative Collaboration: Work collaboratively to create laws that balance constitutional rights with societal norms.

- International Learning: Study global examples of countries that have legalized same-sex marriage to draft effective and inclusive laws.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's verdict reflects the complexities of legalizing same-sex marriages in India, balancing societal norms and constitutional rights. While the current legal framework does not permit same-sex marriage, steps such as recognizing civil unions, amending existing laws, and fostering social acceptance can pave the way for greater inclusivity.

Introduction

- Global Tradition of Marriage:

- Marriage is a universal tradition, symbolizing a union with social, cultural, and religious significance.

- The Foreign Marriage Act, 1969 bridges the gap between Indian citizens and foreigners, providing a legal framework for such marriages.

- Objective of the Act:

- To solemnize marriages between Indian citizens and foreigners or Indian citizens marrying abroad.

- The Act ensures uniformity and addresses conditions not covered under personal or domestic laws.

Key Features of the Foreign Marriage Act, 1969

- Applicability: Covers marriages where at least one party is an Indian citizen and applies to marriages solemnized outside Indian territory.

- Conditions for Valid Marriage:

- Monogamy: Neither party should have a living spouse.

- Mental Stability: Both parties should be of sound mind and capable of giving valid consent.

- Minimum Age: Bridegroom must be at least 21 years, and the bride at least 18 years.

- Prohibited Relationships: Marriage cannot take place within prohibited degrees of relationship unless permitted by customs.

- Notice and Publication: Parties must give notice of intended marriage to the Marriage Officer, and the notice is published in the Marriage Notice Book for public inspection.

- Objection to Marriage: Objections can be raised within 30 days of notice publication. The Marriage Officer must resolve objections before proceeding with solemnization.

- Certificate of Marriage: After fulfilling all conditions, a Certificate of Marriage is issued, serving as conclusive proof of marriage.

- Recognition of Foreign Marriages: Marriages solemnized under foreign laws are recognized under Section 23, provided they meet the provisions of the Act and are registered.

Challenges in Foreign Marriages

- Abandonment of Spouse: Rising cases of NRI husbands abandoning their wives post-marriage.

- Domestic Violence: Women face physical or emotional abuse after moving abroad post-marriage.

- Bigamy: Instances of husbands being already married under foreign laws, causing trauma to the spouse.

- Dowry Issues: Persistent dowry demands, both pre- and post-marriage.

- Lenient Foreign Laws: NRI husbands take advantage of lenient divorce laws abroad, leaving wives without legal remedies in India.

Proposed Solutions

- Government Initiatives: Support from the Ministry of External Affairs and National Commission for Women, along with awareness programs.

- Awareness Campaigns: Workshops and seminars like the National Consultation on NRI Marriages educate women about their rights.

- Stronger Legal Provisions: Amendments to include strict penalties for offenses in foreign marriages and facilitate relief under Indian laws.

Comparison with Other Marriage Laws

- Foreign Marriage Act vs. Special Marriage Act:

- Foreign Marriage Act applies to marriages involving foreigners or solemnized abroad.

- Special Marriage Act applies within Indian territory.

- Relief under the Foreign Marriage Act is governed by the Special Marriage Act.

- Foreign Marriage Act vs. Hindu Marriage Act:

- The Hindu Marriage Act is exclusive to Hindus and applicable only within Indian territory.

- The Foreign Marriage Act is secular, allowing inter-religious and inter-cultural marriages.

Critical Analysis

- Lack of Specific Provisions: The Act lacks provisions for divorce, maintenance, and succession laws specific to foreign marriages.

- Reliance on Other Acts: Couples must rely on Special Marriage Act provisions for matrimonial relief, leading to potential legal conflicts.

- Limited Penalties: Penalties apply only to Indian citizens, leaving foreign offenders unaccountable.

Conclusion

The Foreign Marriage Act, 1969 has been instrumental in providing a legal framework for marriages involving Indian citizens and foreigners. However, its dependency on other laws for relief highlights the need for amendments. Strengthening the Act with provisions for divorce, maintenance, and succession would address existing gaps, ensuring better protection for parties in foreign and inter-racial marriages.

Introduction

- Definition:

- Restitution of conjugal rights refers to the legal process by which an aggrieved spouse can seek the court’s intervention to compel their partner to resume cohabitation and fulfill marital duties.

- This remedy is available under both Hindu law (Section 9 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955) and Muslim law, albeit with differences in approach and application.

- Purpose:

- To preserve the sanctity of marriage.

- To protect the rights of the aggrieved spouse.

Restitution of Conjugal Rights Under Hindu Law

- Legal Provision: Governed by Section 9 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. Either spouse can file a petition if the other unjustifiably withdraws from their society.

- Conditions for Relief:

- Legal Marriage: The marriage must be valid and recognized under Hindu law.

- Unjustifiable Withdrawal: One spouse must have withdrawn from cohabitation without reasonable cause.

- Good Faith by Aggrieved Party: The spouse filing for restitution must genuinely seek to continue the marital relationship.

- Court Proceedings:

- A petition is filed in the district court.

- The burden of proof lies on the aggrieved spouse to demonstrate unjustified withdrawal.

- The court evaluates evidence and circumstances to decide on the decree.

- Objective:

- To restore marital companionship.

- To maintain the unity and sanctity of the marriage.

- Judicial Interpretation: Courts emphasize that restitution should not be enforced if it leads to coercion or violates fundamental rights.

Restitution of Conjugal Rights Under Muslim Law

- Legal Basis: Not codified but rooted in Muslim personal law and Quranic principles. A lawsuit must be filed to seek this remedy.

- Eligibility:

- Applicable only in valid marriages.

- Relief is discretionary and depends on the facts and circumstances.

- Conditions for Relief:

- Valid Reason for Refusal: If a wife refuses to live with her husband, she must provide a valid reason (e.g., cruelty or breach of marital obligations).

- Husband's Obligations: The husband must fulfill his duties (e.g., maintenance, kind treatment) before seeking restitution.

- Court’s Approach: Muslim law emphasizes equity and fairness. Courts generally require strict evidence from the husband to prove unjustified withdrawal by the wife.

- Role of Quranic Guidance: While the husband has authority, the Quran instructs him to treat his wife kindly and justly, aligning the remedy with Islamic teachings.

Comparison of Hindu and Muslim Law on Restitution

| Aspect | Hindu Law | Muslim Law |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Basis | Section 9 of Hindu Marriage Act | Principles of Muslim personal law |

| Initiation | Petition in district court | Filing a lawsuit |

| Validity of Marriage | Marriage must be legal and recognized | Marriage must be valid under Muslim law |

| Grounds for Refusal | Cruelty, reasonable cause | Cruelty, breach of duties by husband |

| Court's Role | Statutory interpretation | Discretionary, equitable relief |

| Objective | Restore cohabitation | Ensure marital harmony and fairness |

Conclusion

Restitution of conjugal rights aims to balance the sanctity of marriage with individual rights. While Hindu law provides a structured statutory remedy, Muslim law emphasizes equity and compliance with Islamic principles. Both systems ensure that restitution does not result in coercion or injustice, protecting the welfare of spouses.

3.6 Divorce Under Muslim Law

- Types of Divorce:

- Extra-Judicial Divorce:

- By Husband:

- Talaq-ul-Sunnat (approved by Prophet):

- Ahsan: Single pronouncement, revocable during iddat period.

- Hasan: Three pronouncements in three tuhr periods.

- Talaq-ul-Biddat (Triple Talaq): Instant, now criminalized under Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, 2019.

- Talaq-ul-Sunnat (approved by Prophet):

- By Wife:

- Talaq-e-Tafweez: Divorce by delegated authority from husband.

- Lian: Based on false allegations of adultery by husband.

- By Mutual Consent:

- Khula: Wife initiates divorce by giving compensation.

- Mubarat: Mutual agreement to separate.

- By Husband:

- Judicial Divorce: Governed by Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939. Grounds for wife include:

- Husband missing for 4 years.

- Failure to maintain for 2 years.

- Husband imprisoned for 7 years or more.

- Husband impotent or insane.

- Husband treats wife with cruelty.

- Extra-Judicial Divorce:

3.7 Legal Effects of Divorce

Under Hindu Law:

- Termination of Rights:

- Mutual rights of inheritance cease.

- Both parties are free to remarry.

- Maintenance: Courts may award alimony under Section 25 of Hindu Marriage Act.

- Custody: Governed by Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956.

- Property: Division depends on legal ownership and maintenance rights.

Under Muslim Law:

- Termination of Marriage: Post iddat period, parties are free to remarry.

- Dower (Mahr): If not paid earlier, becomes due upon divorce.

- Maintenance: During iddat period; husband’s obligation ends post-iddat.

- Inheritance: Ceases upon divorce becoming irrevocable.

- Custody: Governed by Muslim Personal Law (Shariat).

3.8 Legitimacy of Children Out of Different Types of Wedlock

- Establishment of Maternity and Paternity:

- Maternity:

- Under Sunni Law: Established with the woman who gives birth, regardless of wedlock.

- Under Shia Law: Established only if birth occurs within a lawful marriage.

- Paternity: Requires valid or irregular marriage but not a void marriage. A child born in wedlock is presumed legitimate unless proven otherwise.

- Maternity:

- Doctrine of Acknowledgement (Ikrar-e-Nasab):

- Used when legitimacy of a child is in doubt.

- A man can acknowledge a child as his legitimate offspring.

- Conditions:

- Acknowledger must be older than child by 12.5 years.

- Child should not be known as another man's child.

- Acknowledgement must indicate legitimacy.

- Effects of Acknowledgment:

- Child inherits rights from father.

- Mother gains status of legal wife with inheritance rights.

- Difference Between Adoption and Acknowledgment:

| Aspect | Acknowledgment | Adoption |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Status | Recognizes biological relationship. | Creates a new legal parent-child bond. |

| Basis | Biological connection presumed. | Unrelated child is brought into the family. |

| Inheritance Rights | Child inherits from acknowledger. | Child inherits as a natural heir. |

| Practice in Muslim Law | Allowed under acknowledgment doctrine. | Prohibited under Islamic law. |

Personal laws refer to laws that are specific to a particular religion and govern matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, and family relationships. These laws are deeply rooted in the traditions, customs, and beliefs of each religion and have evolved over time to adapt to changing social norms.

1. Definition of Personal Laws

- Personal laws are a set of rules that apply based on religion and cultural practices.

- They regulate private matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, property rights, and adoption.

2. Basis of Personal Laws

- Derived from ancient customs, scriptures, or religious teachings.

- Serve as the legal framework for maintaining harmony in religious and community practices.

3. Examples of Personal Laws

- Hindu Law:

- Governed by the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, and Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956.

- Addresses issues like intestate succession (inheritance without a will), divorce, and adoption.

- Women were given equal rights to property after the 2005 amendment.

- Muslim Law:

- Governed by the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937.

- Based on the Quran and interpretations under Shia and Sunni schools.

- Does not recognize adoption like Hindu law but allows guardianship.

4. Key Features of Personal Laws

- Respect for Religious Sentiments: Designed to reflect the beliefs and traditions of the community.

- Customized for Each Religion:

- Hindu law allows adoption and recognizes ancestral property.

- Muslim law emphasizes joint property and inheritance under Shariat law.

- Evolved Over Time: Amendments have been made to ensure equality and modern relevance, such as equal property rights for women in Hindu law.

5. Challenges with Personal Laws

- Complexity: Different laws for different religions make legal processes complicated.

- Gender Inequality: Historically, some personal laws have been criticized for favoring men (e.g., unequal inheritance rights for women).

- Secularism: Critics argue for a uniform set of laws for all citizens to ensure equality.

6. Need for Uniform Civil Code (UCC)

- Article 44 of the Indian Constitution calls for a Uniform Civil Code.

- UCC would provide a common set of laws for all citizens, regardless of religion, ensuring equality and simplicity.

7. Conclusion

Personal laws are essential for respecting religious diversity in a country like India. However, they can create legal complexities and inconsistencies. Moving towards a Uniform Civil Code could simplify these laws and promote equality among all citizens, emphasizing that we are Indians first.

Personal laws refer to laws that are specific to a particular religion and govern matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, and family relationships. These laws are deeply rooted in the traditions, customs, and beliefs of each religion and have evolved over time to adapt to changing social norms.

1. Definition of Personal Laws

- Personal laws are a set of rules that apply based on religion and cultural practices.

- They regulate private matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, property rights, and adoption.

2. Basis of Personal Laws

- Derived from ancient customs, scriptures, or religious teachings.

- Serve as the legal framework for maintaining harmony in religious and community practices.

3. Examples of Personal Laws

- Hindu Law:

- Governed by the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, and Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956.

- Addresses issues like intestate succession (inheritance without a will), divorce, and adoption.

- Women were given equal rights to property after the 2005 amendment.

- Muslim Law:

- Governed by the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937.

- Based on the Quran and interpretations under Shia and Sunni schools.

- Does not recognize adoption like Hindu law but allows guardianship.

4. Key Features of Personal Laws

- Respect for Religious Sentiments: Designed to reflect the beliefs and traditions of the community.

- Customized for Each Religion:

- Hindu law allows adoption and recognizes ancestral property.

- Muslim law emphasizes joint property and inheritance under Shariat law.

- Evolved Over Time: Amendments have been made to ensure equality and modern relevance, such as equal property rights for women in Hindu law.

5. Challenges with Personal Laws

- Complexity: Different laws for different religions make legal processes complicated.

- Gender Inequality: Historically, some personal laws have been criticized for favoring men (e.g., unequal inheritance rights for women).

- Secularism: Critics argue for a uniform set of laws for all citizens to ensure equality.

6. Need for Uniform Civil Code (UCC)

- Article 44 of the Indian Constitution calls for a Uniform Civil Code.

- UCC would provide a common set of laws for all citizens, regardless of religion, ensuring equality and simplicity.

7. Conclusion

Personal laws are essential for respecting religious diversity in a country like India. However, they can create legal complexities and inconsistencies. Moving towards a Uniform Civil Code could simplify these laws and promote equality among all citizens, emphasizing that we are Indians first.

1. Concept of Personal Laws

- Definition: Personal laws are specific to each religion and help regulate relationships in families and communities.

-

Examples:

- Hindu laws like the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, and Hindu Succession Act, 1956.

- Muslim laws like the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937.

- Significance: These laws respect the religious beliefs and traditions of each community while also adapting to modern changes, like giving women equal property rights.

2. Types of Families

A. Based on Lineage (Who Inherits Property and Family Name):

-

1. Matrilineal Families:

- Definition: Lineage and inheritance are traced through the mother’s side.

- Characteristics:

- Property passes from mother to daughter.

- Children belong to the mother’s family.

- Example: Found in certain communities in Kerala, like the Nairs and Khasi tribes of Meghalaya.

-

2. Patrilineal Families:

- Definition: Lineage and inheritance are traced through the father’s side.

- Characteristics:

- Property is passed from father to son.

- Children belong to the father’s family.

- Example: Common in most Indian societies.

B. Based on Residence (Where the Family Lives After Marriage):

-

1. Matrilocal Families:

- Definition: The husband moves to the wife’s family after marriage.

- Characteristics:

- The wife’s family provides residence and support.

- Often linked to matrilineal systems.

- Example: Practiced by some tribal communities in Northeast India.

-

2. Patrilocal Families:

- Definition: The wife moves to the husband’s family after marriage.

- Characteristics:

- The husband’s family provides residence and support.

- Often linked to patrilineal systems.

- Example: Common in Hindu and Muslim families in India.

C. Based on Authority (Who Has Decision-Making Power):

-

1. Matriarchal Families:

- Definition: The mother or eldest female is the head of the family.

- Characteristics:

- Women control property and family decisions.

- Rare in most societies but present in matrilineal communities.

- Example: Khasi and Garo tribes in Meghalaya.

-

2. Patriarchal Families:

- Definition: The father or eldest male is the head of the family.

- Characteristics:

- Men make most family decisions.

- Common in most Indian families.

- Example: Typical in Hindu, Muslim, and other patriarchal societies.

1. Hindu Law

Hindu law is one of the oldest legal systems in the world and is rooted in the concept of Dharma. It governs the lifestyle, customs, and duties of Hindus. The laws were originally based on religious texts and practices.

Origin of Hindu Law

- Based on Dharma:

- Dharma represents the way of life for Hindus, covering every aspect from birth to death.

- Kings in ancient times governed based on Dharma, ensuring laws aligned with it.

- Customs and Practices:

- Hindu law evolved from the customs followed by people over time.

Sources of Hindu Law

Sources are divided into two categories: Ancient Sources and Modern Sources.

A. Ancient Sources

- Shruti (What is Heard):

- Derived from the word "Shur," meaning to hear.

- Refers to the four Vedas: Rigveda, Samveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda.

- These texts were recited by Brahmins, considered knowledgeable, and formed the foundation of Hindu law.

- Smriti (What is Remembered):

- Derived from "Smri," meaning to remember.

- Smritis were written by sages based on the Shrutis.

- Two main types:

- Dharmasastras: Focused on moral conduct.

- Dharmasutras: Covered government, caste, economic affairs, and social relationships.

- Famous examples: Manusmriti (first law book) and Yajnavalkya Smriti.

- Digests and Commentaries:

- Written by scholars to explain and interpret Smritis.

- Examples:

- On Manusmriti: Manubhasya by Medhatithi.

- On Yajnavalkya Smriti: Mitakshara by Vigneshwara.

- Customs:

- Traditions practiced over generations and accepted as law.

- Recognized by courts if they are valid, continuous, widely followed, and not harmful to society.

- Types of customs:

- Local customs: Specific to a region.

- Class customs: Followed by a specific group.

- Family customs: Binding on family members.

B. Modern Sources

- Justice, Equity, and Good Conscience:

- Judges used fair judgment in cases without existing laws.

- Based on fair play and justice but lacked uniformity.

- Legislation:

- Acts passed by Parliament codifying Hindu laws.

- Examples:

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955.

- Hindu Succession Act, 1956.

- Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956.

- Precedents:

- Courts follow decisions made in earlier cases to ensure consistency.

- Supreme Court decisions are binding on lower courts.

Schools of Hindu Law

- 1. Mitakshara School:

- Based on the commentary by Vigneshwara on Yajnavalkya Smriti.

- Focuses on rituals, marriages, and rites of pregnancy.

- Sub-schools:

- Banaras School: Northern India.

- Mithila School: Bihar.

- Bombay School: Gujarat and Maharashtra.

- Madras School: Southern India.

- 2. Dayabhaga School:

- Focused on Bengal and Assam.

- Emphasizes logic and reason over customs.

- Broadened the list of heirs in inheritance laws.

2. Muslim Law

Muslim law is rooted in the teachings of the Quran and Sunnah and governs the lives of Muslims in matters like marriage, divorce, and inheritance.

Origin of Muslim Law

- Divine Origin:

- Based on Allah’s commands revealed to Prophet Muhammad.

- Developed Through Practices:

- Includes traditions and customs adapted to evolving societal norms.

Sources of Muslim Law

Sources are divided into Primary Sources and Secondary Sources.

A. Primary Sources

- Quran:

- Holy book containing Allah’s commands.

- Covers rules for personal conduct, family matters, and social behavior.

- Sunnah:

- Refers to the practices and sayings of Prophet Muhammad.

- Acts as a guide when the Quran is silent on an issue.

B. Secondary Sources

- Ijma (Consensus):

- Agreement among Islamic jurists on a legal issue.

- Sunni jurists consider it a primary source, while Shia jurists see it as secondary.

- Qiyas (Analogical Deduction):

- Applying reasoning to solve new issues by drawing analogies with existing rules in the Quran and Sunnah.

Schools of Muslim Law

- 1. Hanafi School:

- Most liberal and widely followed in North India.

- Focuses on rational deduction.

- 2. Maliki School:

- Followed in parts of Africa and the Middle East.

- Gives importance to practices in Medina, where Prophet Muhammad lived.

- 3. Hanbali School:

- Orthodox and strict in following the Quran and Sunnah.

- Liberal in trade-related matters.

- 4. Shafi School:

- Followed in Yemen, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia.

- Relies on Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas but uses Qiyas less frequently.

Conclusion

Hindu and Muslim laws have evolved from religious texts, customs, and practices. They have been shaped over centuries by scholars, judges, and legislative bodies. Understanding their origins, sources, and schools helps highlight the richness and diversity of India’s legal system.

1. Shia Law

- Origin:

- Derived from the followers of Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of Prophet Muhammad.

- Shia Muslims believe that leadership (Imamat) should remain within the Prophet’s family.

- Sources:

- Primary: Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and reason (Aql).

- Unique Features:

- Greater reliance on reasoning (Ijtihad).

- Limited acceptance of Ijma (consensus) unless by specific Imams.

- Key Schools:

- Imamiyah (Twelvers): Most prominent, based on 12 Imams.

- Ismaili (Seveners): Recognize seven Imams.

- Zaidi (Fivers): Follow five Imams, closer to Sunni practices.

2. Sunni Law

- Origin:

- Sunni Muslims believe in the selection of Caliphs through consensus rather than family lineage.

- They follow the sayings and actions of Prophet Muhammad and his companions.

- Sources:

- Primary: Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas (analogical deduction).

- Unique Features:

- Emphasis on Ijma as a significant source of law.

- Greater reliance on Qiyas (analogical reasoning).

- Key Schools:

- Hanafi: Liberal, emphasizes reasoning and equity.

- Maliki: Values the practices of Medina's people during Prophet Muhammad's time.

- Shafi: Focuses on Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas but uses Qiyas conservatively.

- Hanbali: Strict, emphasizes Quran and Sunnah over analogical reasoning.

Key Differences Between Shia and Sunni Law

| Aspect | Shia Law | Sunni Law |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership | Belief in Imams as divinely appointed leaders. | Leadership by consensus (Caliphate). |

| Sources of Law | Quran, Sunnah, Ijma (by Imams), Aql (reason). | Quran, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas (analogical deduction). |

| View on Ijma | Limited to the decisions of Imams. | Broader consensus among jurists. |

| Role of Reasoning | High reliance on reasoning (Ijtihad). | Reasoning is secondary to Quran and Sunnah. |

| Marriage Laws | Temporary Marriage (Mutah) is allowed. | Temporary marriage is not allowed. |

| Inheritance | Females may receive a fixed share depending on the Imam's ruling. | Clear division according to Quranic guidelines. |

| Prayer Practices | Combine prayers (e.g., Zuhr and Asr together). | Perform five separate prayers daily. |

| Legal Interpretation | Dynamic, depends heavily on Imam’s interpretation. | Conservative, follows traditional methods. |

Conclusion

While both Shia and Sunni laws derive their principles from the Quran and Sunnah, they differ in interpretation, sources, and practices. These differences reflect their unique historical development and cultural influences. Understanding these distinctions is vital for comprehending the diversity within Islamic law.

1. Understanding Article 44 of the Indian Constitution

- Directive Principle of State Policy:

- Article 44 states that the state shall strive to implement a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) across India.

- This aims to replace personal laws based on religion with a common set of rules governing personal matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, and adoption.

- Not Enforceable by Law:

- As a Directive Principle, it is not a binding legal provision but a guideline for the government to work towards.

2. The Need for Uniform Civil Code

- Equality Under the Law:

- Aims to provide equal rights and eliminate discrimination based on religion or gender.

- Gender Justice:

- Addresses issues like unequal inheritance rights, triple talaq, and child marriage, ensuring fairness for women.

- National Integration:

- Promotes a unified legal framework to foster national unity and reduce divisions based on religious laws.

- Simplification of Laws:

- Reduces complexity by replacing multiple personal laws with a single set of rules.

3. Drafting a Uniform Civil Code

- Key Areas Covered:

- Marriage and Divorce: Common age of marriage, equal grounds for divorce.

- Inheritance and Succession: Equal property rights for men and women.

- Adoption: Uniform guidelines for adoption across all communities.

- Guardianship: Equal rights for parents in child custody matters.

- Proposed Features of the Draft UCC:

- Gender Neutrality: Eliminates biases against women in personal laws.

- Religious Neutrality: Ensures that no community’s beliefs dominate others.

- Human Rights Alignment: Incorporates principles of equality and dignity from international human rights standards.

4. Judicial Pronouncements Supporting UCC

- Shah Bano Case (1985):

- Emphasized the need for UCC to uphold women's rights and national integration.

- Sarla Mudgal Case (1995):

- Urged the government to expedite UCC implementation.

- Shayara Bano Case (2017):

- Abolished triple talaq, reigniting discussions about UCC.

5. Arguments in Favor of UCC

- Promoting Equality:

- Eliminates discrimination in personal laws.

- Ensures equal treatment for men and women, irrespective of religion.

- Empowering Women:

- Corrects gender biases like unequal inheritance and child marriage.

- Streamlining Legal Processes:

- Simplifies the legal system, reducing court backlog and disputes.

- National Unity:

- Prioritizes citizenship over religious identity in legal matters.

- Social Modernization:

- Aligns personal laws with contemporary values, including LGBTQ+ rights.

Conclusion

The Uniform Civil Code is a complex yet essential step towards equality and national integration. While Article 44 envisions a common legal framework, its implementation requires careful consideration of cultural diversity and minority rights. A gradual, inclusive approach can pave the way for a UCC that upholds justice, equality, and social harmony in India.

1. Hindu Marriage Law

- Definition:

- In Hindu law, marriage is considered a sacrament rather than a contract.

- It is a religious duty and one of the 16 samskaras (rites of passage).

- The purpose of Hindu marriage is spiritual union, social cooperation, and procreation.

- Legal Framework:

- Governed by the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955.

- Includes Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists under its ambit (Article 25(2)(b) of the Constitution).

- Key Points:

- Marriage must comply with specific conditions under Section 5 of the Act, such as no existing spouse, sound mind, legal age (21 for men, 18 for women), and absence of prohibited relationships.

- Saptapadi (Seven Steps): A vital ritual where the couple walks seven steps around the sacred fire, marking the binding authority of the marriage.

2. Muslim Marriage Law

- Definition:

- In Muslim law, marriage is a civil contract (Nikahnama), not a sacrament.

- It is a mutual agreement between a man and a woman to live together as husband and wife.

- Legal Framework:

- No codified law governs Muslim marriages; it is based on the Shariat and personal laws.

- Key Points:

- Essential requirements include:

- Ijab (Proposal) and Qubool (Acceptance).

- Mehr (Dower) as consideration for the marriage.

- Free consent of both parties.

- Presence of witnesses (number varies for Shia and Sunni sects).

- Types of Marriages: Sahih (Valid), Fasid (Irregular), and Batil (Void).

- Muta Marriages: Temporary and pleasure-based marriages recognized by Shia Muslims but not Sunni Muslims.

- Essential requirements include:

3. Christian Marriage Law

- Definition:

- Marriage in Christian law is a sacred union performed under religious and civil regulations.

- Legal Framework:

- Governed by the Indian Christian Marriage Act, 1872.

- Includes marriage between Christians and between a Christian and non-Christian (with specific provisions).

- Key Points:

- Marriage must be solemnized by an authorized priest or Marriage Registrar.

- Conditions include:

- Minimum age (21 for men, 18 for women).

- Consent of both parties.

- No existing spouse at the time of marriage.

Conclusion

Marriage is a universal institution, but its definition and interpretation vary across religions in India. While Hindu and Christian laws view marriage as a sacred union, Muslim law considers it a civil contract. The Special Marriage Act provides a secular framework for interfaith and inter-caste marriages. The demand for inclusivity, such as recognizing LGBTQIA+ marriages, highlights the need to update and harmonize marriage laws to reflect modern societal values.

1. Both Parties Must Be Hindus

- Requirement: Both individuals must be Hindus at the time of marriage.

- Legal Basis: Section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act.

- Explanation: If one party follows a different religion, the marriage is not valid under this Act.

- Case Law: In Yamunabai Anant Rao Adhav v. Anant Rao Shivaram Adhav (1988), the Supreme Court ruled that a marriage between a Hindu and a Christian was void under this Act.

2. Soundness of Mind and Legal Consent

- Requirement:

- Both parties must be capable of giving legal consent.

- Neither party should suffer from unsoundness of mind, mental disorder, or insanity.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(ii) of the Act.

- Key Points:

- If a party is incapable of giving consent or has a mental condition that makes them unfit for marriage or bearing children, the marriage can be annulled.

- Case Law: In Alka Sharma v. Chandra Sharma (1991), the court annulled a marriage where the woman exhibited irrational behavior, making her unfit for marital life.

3. Monogamy

- Requirement: Neither party should have a living spouse at the time of marriage.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(i) and Section 17 of the Act.

- Key Points:

- Second marriages are void unless the first marriage has ended due to death or divorce.

- Penalties for bigamy include imprisonment and fines under Sections 494 and 495 of the Indian Penal Code.

4. Age Requirements

- Requirement:

- The bride must be at least 18 years old, and the groom must be at least 21 years old.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(iii) of the Act.

- Key Points:

- Marriages that violate age requirements are not void but are punishable under Section 18 of the Act with imprisonment, fines, or both.

- Case Law: In P. Venkataramana v. State (1977), it was held that violation of age requirements does not invalidate the marriage but is punishable.

5. Prohibition of Sapinda Relationships

- Requirement: Marriage within Sapinda relationships is prohibited unless allowed by custom.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(v) and Section 3(f) of the Act.

- Key Points:

- Sapinda relationships extend up to three generations on the mother’s side and five generations on the father’s side.

- Violations are punishable with imprisonment or fines under Section 18.

6. Prohibited Degrees of Relationship

- Requirement: Marriage between individuals within prohibited degrees of relationship is not allowed unless custom permits.

- Legal Basis: Section 5(iv) and Section 3(g) of the Act.

- Key Points:

- Prohibited relationships include close family members like siblings, ascendants, and descendants.

- Case Law: In Balu Swami Reddiar v. Balakrishna (1956), the court declared a marriage void as it violated the prohibition on close familial connections.

7. Solemnisation of Marriage According to Customary Rites

- Requirement: Marriage must be solemnised according to the customary rites and ceremonies of either party.

- Legal Basis: Section 7 of the Act.

- Key Points:

- The Saptapadi (Seven Steps) ritual is essential, and the marriage is considered complete when the seventh step is taken.

- Case Law: In Bibba v. Ramkall (1982), the court emphasized the need for proper ceremonial rites to validate the marriage.

1. Recognized Forms (Valid)

- Brahma Marriage: The bride’s father gives her as a gift to a groom with good character.

- Daiva Marriage: The bride is given to a priest performing a religious ritual.

- Arsha Marriage: The groom gives symbolic gifts like cows to the bride’s father.

- Prajapatya Marriage: Marriage for fulfilling familial and societal duties.

2. Unrecognized or Invalid Forms

- Asura Marriage: The bride is given in exchange for money or gifts.

- Gandharva Marriage: Marriage based solely on mutual love and consent without rituals.

- Rakshasa Marriage: Marriage by force or abduction.

- Paisacha Marriage: The bride is married without her consent, often in a vulnerable state.

Conclusion

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, ensures that marriages follow essential conditions for validity, including mutual consent, legal age, and adherence to traditional rites. Understanding traditional categories helps appreciate the evolution of Hindu marriage practices.

1. Proposal and Acceptance (Ijab and Qubul)

- Requirement:

- There must be an offer (Ijab) by one party and acceptance (Qubul) by the other.

- Both must occur in the same meeting.

- Importance: A delayed or deferred acceptance invalidates the marriage.

2. Competency of Parties

- Legal Age:

- Puberty is considered the age of legal marriage, generally presumed at 15 years unless proven otherwise.

- Case Law: In Muhammad Ibrahim v. Atkia Begum, it was held that puberty is reached at 15 years unless earlier maturity is proven.

- Guardians for Minors:

- If a party is below the age of puberty, the guardian's consent is necessary.

- Guardians include the father, paternal grandfather, mother, or other male family members.

- Sound Mind: Both parties must be mentally capable of understanding the contract. A lunatic can marry during periods of sanity.

- Muslim Faith: Both parties must be Muslims. Inter-sect marriages are allowed, e.g., between Sunni and Shia Muslims.

3. Free Consent

- Requirement: Consent must be free and voluntary. Coercion, fraud, or mistake of fact makes the marriage void.

- Case Law: In Mohiuddin v. Khatijabibi, the court ruled that free consent is a cornerstone of a valid Muslim marriage.

4. Dower (Mahr)

- Definition: A monetary or property consideration given by the groom to the bride.

- Purpose: Ensures financial security for the bride.

- Case Law: In Nasra Begum v. Rizwan Ali, the court held that dower must be settled before cohabitation.

5. Freedom from Legal Disability

- Absolute Prohibitions (Void Marriage):

- Consanguinity: Prohibition on marrying close blood relatives.

- Affinity: Prohibition on marrying close relatives by marriage.

- Fosterage: Prohibition on marrying foster relatives.

- Relative Prohibitions (Irregular Marriage):

- Unlawful Conjunction: Marrying two closely related women at the same time.

- Polygamy: Marrying more than four wives simultaneously.

- Witness Absence: Sunni law requires witnesses.

- Marriage During Iddat: Waiting period after divorce or husband’s death.

6. Registration of Muslim Marriages

- Not Mandatory: Islamic law does not require registration.

- Encouraged: Registration provides legal documentation.

- Case Law: In Seema v. Ashwani Kumar, the Supreme Court emphasized registering all marriages to ensure legal proof.

1. Valid Marriage (Sahih)

- Definition: Fulfills all legal and religious requirements.

- Key Features:

- Free consent.

- Competent parties.

- Absence of prohibitions.

2. Void Marriage (Batil)

- Definition: Does not meet essential conditions.

- Examples:

- Marriage within prohibited degrees of consanguinity or fosterage.

- Marrying someone already married under Shia law.

- Consequence: Void ab initio (from the beginning).

3. Irregular Marriage (Fasid)

- Definition: Violates relative prohibitions but can be rectified.

- Examples:

- Marriage without witnesses (in Sunni law).

- Marriage during the Iddat period.

- Fifth marriage while four wives are still alive.

- Consequence: Becomes valid after rectifying irregularities.

Special Types of Marriages

1. Muta Marriage (Temporary Marriage)

- Definition: A temporary marriage for a fixed period and specific consideration.

- Key Features:

- Not practiced by Sunni Muslims.

- Practiced by Shia Muslims.

- Ends when the stipulated period expires.

2. Nikah Halala

- Definition: A practice where a divorced woman marries another man and then divorces him to remarry her first husband.

- Purpose: Observed under specific interpretations of Sharia law after a triple talaq.

- Controversy: Widely criticized for being exploitative and against women's rights.

Conclusion

Muslim marriage is a deeply significant institution governed by specific legal and religious rules. Essentials like free consent, competency, and adherence to prohibitions ensure the sanctity of the union. While valid marriages reflect adherence to Islamic law, void and irregular marriages demonstrate the consequences of deviation from these principles. Special types like Muta marriages and Nikah Halala add complexity to Islamic matrimonial laws, highlighting the need for understanding and reform in contemporary times.

Key Features of Solemnisation under the Act

1. Applicability

- The Act applies to all individuals in India regardless of their religion (Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, or any other religion).

- It is also applicable to Indian citizens living abroad.

2. Conditions for a Valid Marriage

- Non-Existence of a Living Spouse: Neither party should have an existing living spouse at the time of marriage.

- Capacity to Consent: Both parties must be capable of giving free and informed consent. They should not be suffering from any mental illness that makes them unfit for marriage or procreation.

- Age Requirements: The male must be at least 21 years old, and the female must be at least 18 years old.

- Prohibited Relationships: The parties should not fall within degrees of prohibited relationships unless their customs allow such unions.

3. Notice of Intended Marriage