Administrative Actions: Meaning, Nature, Scope and Significance

Meaning of Administrative Actions

Administrative actions refer to actions taken under administrative law, which deals with the powers and duties of government authorities. These actions are legal measures related to public administrative bodies, aimed at protecting the public and maintaining law and order in society. Unlike legislative or judicial actions, administrative actions are carried out by government authorities as they perform their duties.

When exercising administrative powers, it’s important to follow the principles of natural justice, though this can vary depending on the specific circumstances of each case. Administrative actions ensure that authorities do or do not take certain actions as required.

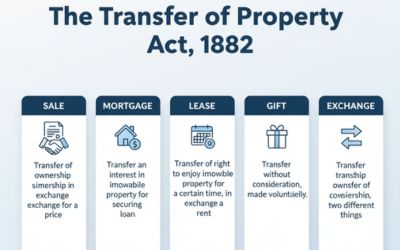

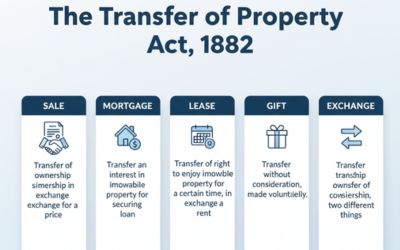

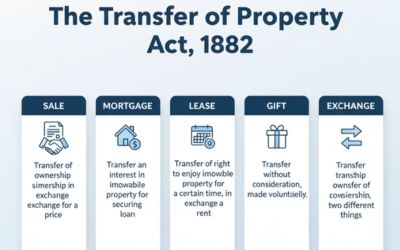

Administrative actions can be categorized into three types:

- Quasi-Legislative (Rule-Making Actions): These involve administrative bodies exercising delegated law-making powers. For example, creating rules like Civil Servant Efficiency Rules 1973 or Conduct Rules.

- Quasi-Judicial (Rule-Decision Actions): These occur when administrative decisions, which involve judicial characteristics, are made. For example, disciplinary actions against students or proceedings against an employee for misconduct.

- Fully Administrative (Rule-Application Actions): These involve applying a legislative rule to a specific case. For example, transferring a civil servant or appointing an inquiry officer.

Nature, Scope, and Significance of Administrative Actions

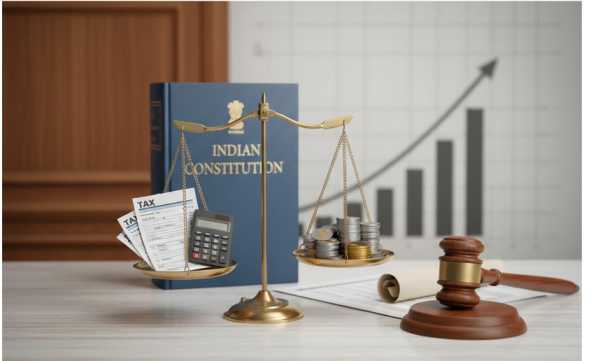

Administrative actions are not always purely administrative, quasi-judicial, or quasi-legislative in nature; they often encompass a wide range of activities. These actions are distinct from legislative and judicial actions and can be either statutory, meaning they have the force of law, or non-statutory. If administrative actions violate the principles of natural justice or infringe upon citizens' rights, the courts have the authority to challenge and nullify such actions.

Given the heavy burden on the judiciary with numerous pending cases, it's impractical for the courts to handle all administrative issues directly. This is why quasi-judicial and quasi-legislative bodies are empowered to address certain matters, reducing the workload on the judiciary. During emergencies, such as wartime, administrative actions by the executive are often the most effective way to manage the situation due to the executive's immediate and decisive powers.

Administrative authorities have the power to act in the public's interest, and these actions are expected to adhere to basic principles of fairness. If an administrative action is unfair or unjust, it can be reviewed by the courts.

Individuals or corporate bodies can challenge administrative actions in court, and such actions are controlled by the judiciary through the issuance of writs. The Supreme Court, under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution, has the power to issue writs to address any violations of fundamental rights by administrative actions.

Case Laws Dealing with Administrative Actions

Sat Pal Singh v. Union of India and Ors.

The petitioner, Sat Pal Singh, was serving as a Lance Naik in the Border Security Force (BSF) and was later promoted to the rank of Head Constable. He, along with other sports participants, was granted special leave and went to his home in Bam Loni, District Rohtak, on September 6, 1995. He was supposed to return to duty on October 17, 1995. Unfortunately, between September 30, 1995, and December 6, 1995, he fell ill.

On December 7, 1995, while attempting to return to his duties, the petitioner took a ride in a civil truck. However, the truck met with an accident, and he was admitted to the Government Hospital Amrit Kaur Byawar. Due to this accident, he could not report back to his Unit. To his surprise, on March 14, 1996, he received an order from the Commandant of the 44th Battalion BSF, removing him from service.

Displeased with this decision, the petitioner filed an appeal seeking reinstatement. However, his appeal was dismissed on December 29, 1997, with the authorities stating that there was no merit in his arguments. After failing to get relief, the petitioner challenged the order in a writ petition under Article 226 of the Constitution of India, arguing that the BSF authorities did not follow the proper procedure as outlined in BSF Rule 22 and Section 11(4) of the Border Security Force Act.

Court's Decision:

The court noted that the BSF authorities opted to take administrative action under Rule 22 of the BSF Rules, leading to the petitioner's dismissal. However, the court found that the authorities handled the case in a casual manner, without properly applying their minds or providing valid reasons for the decision. The court determined that the basic requirements for such an administrative action were not met.

As a result, the court allowed the petition and granted the respondents the freedom to initiate fresh departmental proceedings if they wished. The court directed them to issue a new show-cause notice to the petitioner and give him a fair opportunity to present his case. The respondents were ordered to complete this process and pass appropriate orders within three months from the date of the court's decision.

A.K. Kraipak v. Union of India

In this case, the government advertised for the position of Chief Conservator of Forests. Many candidates applied for the post, including the acting Chief Conservator of Forests. When the interviews were conducted, the acting Chief Conservator was also part of the selection panel.

Another candidate, A.K. Kraipak, filed a case arguing that the selection process was unfair because the acting Chief Conservator, who was also a candidate, was part of the interview panel. Kraipak claimed this created bias against other candidates and violated the principles of fairness under Articles 14 and 16 of the Indian Constitution.

The acting Chief Conservator defended himself, saying he was not present in the panel when his own interview was conducted. However, the court examined the case as an administrative action and assessed the validity of the selection process.

Court's Decision:

The court held that the selection process violated the principles of natural justice. It found that some Assistant Conservators were selected for the senior scale service while others with more than eight years of experience were selected for the junior scale service, which was unfair.

Because the court could not separate the two groups of officers, it set aside the entire selection process. The petitions were allowed, and the selections were nullified. The Union Government and the State Government were also ordered to pay the petitioners' legal costs.

Karnataka Public Service vs B.M. Vijaya Shankar And Ors.

The Karnataka Public Service Commission conducted competitive exams for the state civil services. Candidates were instructed to write their roll numbers only on the front page of the answer sheet in the designated space and not anywhere else inside the answer sheet.

It was clearly stated that candidates must follow these instructions, and violating them could lead to expulsion from the examination or other punishments as deemed fit by the commission. However, one candidate violated these instructions by writing his roll number on every page of the answer sheet. As a result, the commission canceled his paper.

The candidate then challenged the commission's action before the Karnataka Administrative Tribunal, which ordered the commission to evaluate his answer sheet. The tribunal held that since no specific penalty was provided for violating the instructions and the candidate was not given an opportunity to explain his actions, the commission's decision was arbitrary. The commission and the state appealed this decision in court.

Court's Decision:

The court allowed the appeal, setting aside the tribunal's order. It dismissed the candidate's claim, stating that this matter was purely an administrative action, and the commission's decision to cancel the paper was justified.

In Star Enterprises v. City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra Ltd.

In the case of In Star Enterprises v. City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra Ltd. A three-judge bench of the court emphasized that judicial review of administrative actions has expanded significantly in today's context. The state must now justify its actions in various areas of public law, which makes it necessary to record reasons for executive decisions, including the rejection of the highest offer.

The court also noted that providing reasons for such rejections allows for an objective review by higher administrative authorities and through the judicial process. These reasons should be communicated unless there is a clear and justifiable reason not to do so.

Ratnakar Vishwanath Joshi vs Life Insurance Corporation

In the case of Ratnakar Vishwanath Joshi vs Life Insurance Corporation, the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) introduced a scheme to help its employees qualify as Actuaries. This scheme was provided through administrative instructions issued by the Chairman of the Corporation. The petitioners, who were Class I Officers of LIC and beneficiaries of the scheme, argued that the scheme, introduced on July 31, 1971, could not be withdrawn unless done so legally. They challenged the Chairman's decision to revoke the scheme on March 6, 1972.

To succeed in their claim, the petitioners needed to prove that their right to the scheme's benefits was based on law, not just on a contract. The court highlighted that administrative actions or instructions issued by LIC regarding its employees differ significantly from those issued by the government to its servants. Government employees are governed by laws and status, while LIC employees are still bound by contracts.

The court held that the scheme in question was merely an administrative instruction, not a law or regulation with legal force. Therefore, the petitioners did not have a legal right under Article 226 of the Constitution to demand that the scheme could not be withdrawn, nor could they challenge the Chairman's action in withdrawing it. The scheme was viewed as a benefit offered at the discretion of the Corporation, not as an enforceable right.

As a result, the court dismissed the petition, stating that the withdrawal of the scheme was an internal administrative matter of the Corporation. Even if the withdrawal was contrary to regulations, it could not be contested through a writ petition since the scheme itself was not legally enforceable. The petition was dismissed without any order as to costs.

Share

Related Post

Tags

Archive

Popular & Recent Post

Comment

Nothing for now