Tortious Liability of the State and Article 300 of the Constitution

Introduction

Article 300 of the Indian Constitution addresses the tortious liability of the administration. This article is divided into three main parts:

- The first part explains how lawsuits and legal proceedings can be brought by or against the government. It states that the Union of India can be sued under that name, and a State can be sued under the name of that specific State.

- The second part states that the Union of India or a State can be sued in matters related to its functions in the same manner as the Dominion of India or a corresponding Indian State could have been sued before the Constitution was enacted.

- The third part allows the Parliament or a State legislature to create laws that specifically address the matters covered by Article 300(1).

How Article 300 of the Indian Constitution Deals with the Tortious Liability of the State

Article 300 of the Indian Constitution explains how the government can be held responsible for wrongful acts (tortious liability). Here's a simplified breakdown:

- Government's Legal Identity: The Government of India can be sued or can sue under the name "Union of India," and the government of a State can do so under the name of that State. This means both the central and state governments can be involved in legal cases in their official names.

- Continuity of Legal Actions: If legal cases were already ongoing at the time the Constitution came into effect, the Union of India takes the place of the "Dominion of India" (the governing body before the Constitution). Similarly, a State government takes the place of the corresponding province or Indian State involved in such cases.

In simple terms, Article 300 allows people to sue the government just as they could sue the governing bodies before the Constitution came into effect, and it ensures that ongoing cases continue seamlessly with the new government entities.

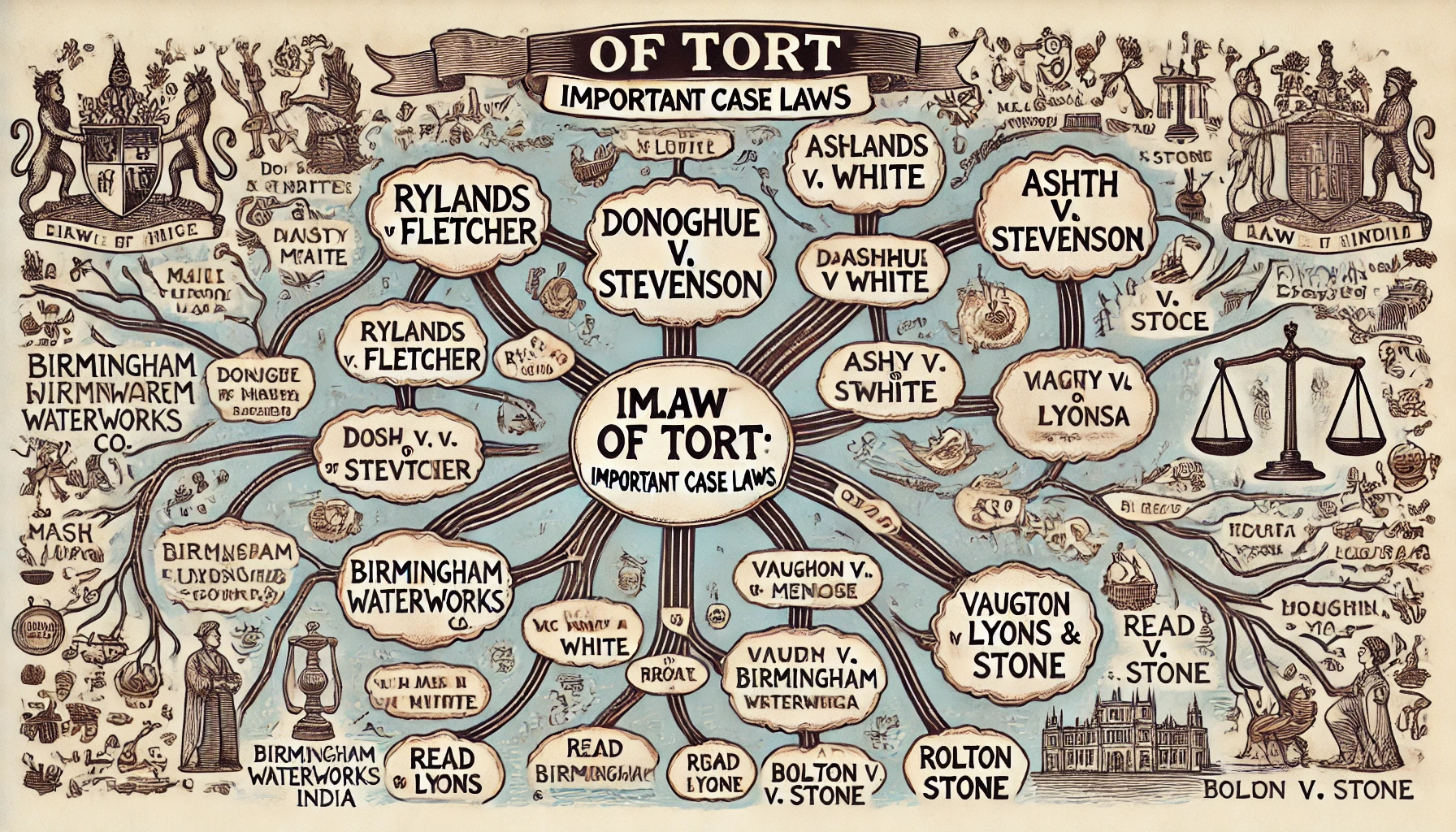

Important Case Laws on the Tortious Liability of the State

P&O Navigation Company v. Secretary of State for India

This was one of the first cases that seriously discussed the idea of Sovereign Immunity in India. In this case, a piece of iron funnel, being carried by workmen repairing a government steamer, fell and hit the plaintiff's horse-drawn carriage, causing injury. The plaintiff sued the Secretary of State for India for the negligence of the government-employed workers. The Calcutta Supreme Court, through the Chief Justice, ruled that the government could be held liable for the actions of its employees when they are performing non-sovereign functions (ordinary, non-governmental duties). However, the government would not be liable for injuries caused while performing sovereign functions (actions taken as part of government duties).

Nobin Chunder Dey v. Secretary of State

In this case, the Calcutta High Court upheld the idea that the government is not liable for actions performed as part of its sovereign functions. The plaintiff, Nobin Chunder Dey, had been wrongfully denied a license to sell certain excisable liquors and drugs, leading to the closure of his business. He sued for damages, but the court rejected his claim, stating that the granting or denial of a license is a sovereign function, which is beyond the scope of tortious liability for the State.

These cases established a clear distinction between sovereign and non-sovereign functions, which has since been the foundation for many legal decisions regarding the liability of the State.

Other Provisions Related to the Tortious Liability of the Administration

- Article 294(4) of the Constitution: This article states that the liability of the Union Government or a State Government can arise from "any contract or otherwise." The term "otherwise" implies that this liability may also extend to tortious acts. Article 300(1) further clarifies the extent of such liability, stating that the liability of the Union of India or State Governments will be the same as that of the Dominion of India and the provinces before the Constitution was enacted.

- Sovereign Immunity in India: Indian law partially adopts the English law concept of government immunity from tortious acts committed by its servants. Traditionally, a distinction is made between "sovereign functions" (for which the state is not liable) and "non-sovereign functions" (for which the state may be liable). The general rule is that the state cannot be sued in its own courts without its consent, particularly when performing sovereign functions.

- Section 80 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908: This section requires that before suing the government, a notice in writing must be given, and a suit can only be instituted after two months have passed since the notice was issued.

- Section 82 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908: This section states that when a court decree is passed against the Union of India or a State, the decree cannot be executed until it remains unsatisfied for three months from the date of the decree.

- Article 112 of the Limitation Act, 1963: This article provides that any suit by or on behalf of the Central Government or a State Government must be filed within 30 years.

These provisions collectively define the scope and limitations of the government's liability in cases of tortious acts, emphasizing the special legal status and protections afforded to government actions.

Share

Related Post

Tags

Archive

Popular & Recent Post

Comment

Nothing for now