Himmat Lal v. Commissioner of Police

Easy English explainer of the 1973 Supreme Court ruling on public meetings, police powers, and Article 19(1)(b).

Quick Summary

Himmat Lal v. Commissioner of Police (AIR 1973 SC 87) is about the right to hold public meetings on streets and the limits on police powers. The Supreme Court said the State cannot abolish the right of assembly by a total ban. It can only regulate with reasonable restrictions for public order.

Issues

- Do powers under the Bombay Police Act, 1951 violate Article 19(1)(b) (right to assemble)?

- Can the State require prior permission and still keep the right meaningful for citizens?

Rules

- The State cannot take away the right of assembly by prohibiting meetings on every public street or place.

- The State may regulate the right through reasonable restrictions in the interest of public order.

- Regulatory rules should help each citizen use streets safely and fairly, not shut the right down.

Arguments

Appellant

- Prior-permission rule and refusals cripple the right to assemble.

- Blanket control on public streets equals an indirect ban.

- Rules exceed “regulation” and fail reasonableness.

State

- Regulation is vital to avoid traffic chaos and violence.

- Past incidents justify stricter control for public order.

- Commissioner’s rule-making power is statutory and necessary.

Judgment (Held)

The Supreme Court upheld Section 33(1)(o) as a valid power to regulate assemblies and processions so that streets can serve everyone. But it struck down Rule 7 framed by the Commissioner of Police, Ahmedabad, because it violated Article 19(1)(b). The State cannot turn regulation into a near-total prohibition.

Ratio Decidendi

- Regulate, don’t abolish: The right to assemble on public streets cannot be wiped out by sweeping bans.

- Reasonable restrictions: Must be tied to public order, clarity, and fairness.

- Rule-making power: Valid when it aids free speech, movement, and assembly for all users of streets.

Why It Matters

This case is core reading for Article 19(1)(b). It draws the line between lawful regulation and unconstitutional prohibition and guides police rule-making across India.

Key Takeaways

- Permission systems must not become blanket denials.

- Rules should be precise, public-order focused, and reviewable.

- Section 33(1)(o) survives; Rule 7 does not.

- Assemblies on streets are a right—balanced with others’ use.

Mnemonic + 3-Step Hook

Mnemonic: “MEET—DON’T DELETE.”

- Step 1: Check if the rule aids assembly or kills it.

- Step 2: Link limits to public order and fairness.

- Step 3: Strike rules that become hidden bans.

IRAC Outline

Issue

Do police rules and refusals unlawfully curb Article 19(1)(b) by turning regulation into prohibition?

Rule

State may regulate with reasonable restrictions for public order; cannot abolish assembly rights on all streets.

Application

Section 33(1)(o) helps manage streets for all. Rule 7 overreached and chilled meetings beyond what public order needs.

Conclusion

Section valid; Rule 7 void. Regulation cannot become a disguised ban.

Glossary

- Article 19(1)(b)

- Right to assemble peaceably and without arms.

- Reasonable Restriction

- A fair, proportional limit serving public order or similar aims.

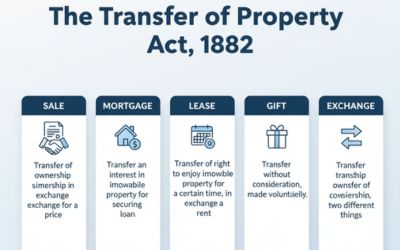

- Regulation vs Prohibition

- Regulation guides how the right is used; prohibition removes it.

- Public Order

- Safety and peace on streets so all can use them.

FAQs

Related Cases

Assembly & Speech

Use with cases balancing street use, speech, and public order under Article 19.

Police Power Limits

Compare with rulings that limit discretion and prevent disguised bans.

Share

Related Post

Tags

Archive

Popular & Recent Post

Comment

Nothing for now